Art and Science II: The Great Psychotherapy Debate

I

For the better part of a year I have been reading Bruce Wampold’s book, The Great Psychotherapy Debate. It’s a white paper examining the evidence for two competing models of interpreting the research on outcomes in psychotherapy. The competing models for interpreting the research are The Medical Model and The Contextual Model.

The Medical Model posits that mental illnesses are like any other disease. In medicine, to treat a disease, we develop treatments with specific ingredients that remedy the particular deficits that cause the symptoms.

The Contextual Model posits that treatments with a cogent rationale accepted by the client, administered by a clinician who the client has a therapeutic relationship with, and involving therapeutic actions that the client expects will help, will lead to a health-promoting change.

The book frames this examination by using the ideas of one of my favorite philosophers of science, Imre Lakatos. It outlines how these two models act as competing research programmes. To get an idea of what that means, you can listen to Lakatos describe his theory on the philosophy of science in this lecture he gave to the BBC:

Philosophers of science argue about what should be considered science vs what should be considered pseudoscience. This is called “the demarcation problem.” Karl Popper believed the most important part of the demarcation problem was that a theory must be falsifiable to be called science (for a great critique of Popper’s position see fakenous’ article). Thomas Kuhn described science in a more sociological way, where “normal science” is disrupted by anomalies which led to the paradigm shift of a scientific revolution.

Lakatos’ view on science is to call something a scientific research programme if it has theories that explain observations and has had novel predictions that could have been falsified. Various research programmes exist at the same time, each with a hard core of theories that cannot be abandoned without abandoning the programme altogether. This hard core is protected by more modest and specific auxiliary hypotheses which help interpret data which seems anomalous. These auxiliary hypotheses can be generated or abandoned as needed. A research programme is progressive if it’s changes to its auxiliary hypotheses help it explain and predict new data and degenerative if it has been doing a poor job at explaining/predicting new data.

This view was an attempt to blend the normative views of Popper with the revolutionary structure described by Kuhn. But Lakatos thought Kuhn’s version of “normal science” and “revolution” were oversimplified, instead describing research programmes gaining adherents if they were more progressive rather than spurring a radical paradigm shift. His demarcation involves calling ‘science’ that which has a history of novel predictions (a programme) and which is progressive (updating in a successful way) in its ongoing explanations of and predictions for incoming data.

II

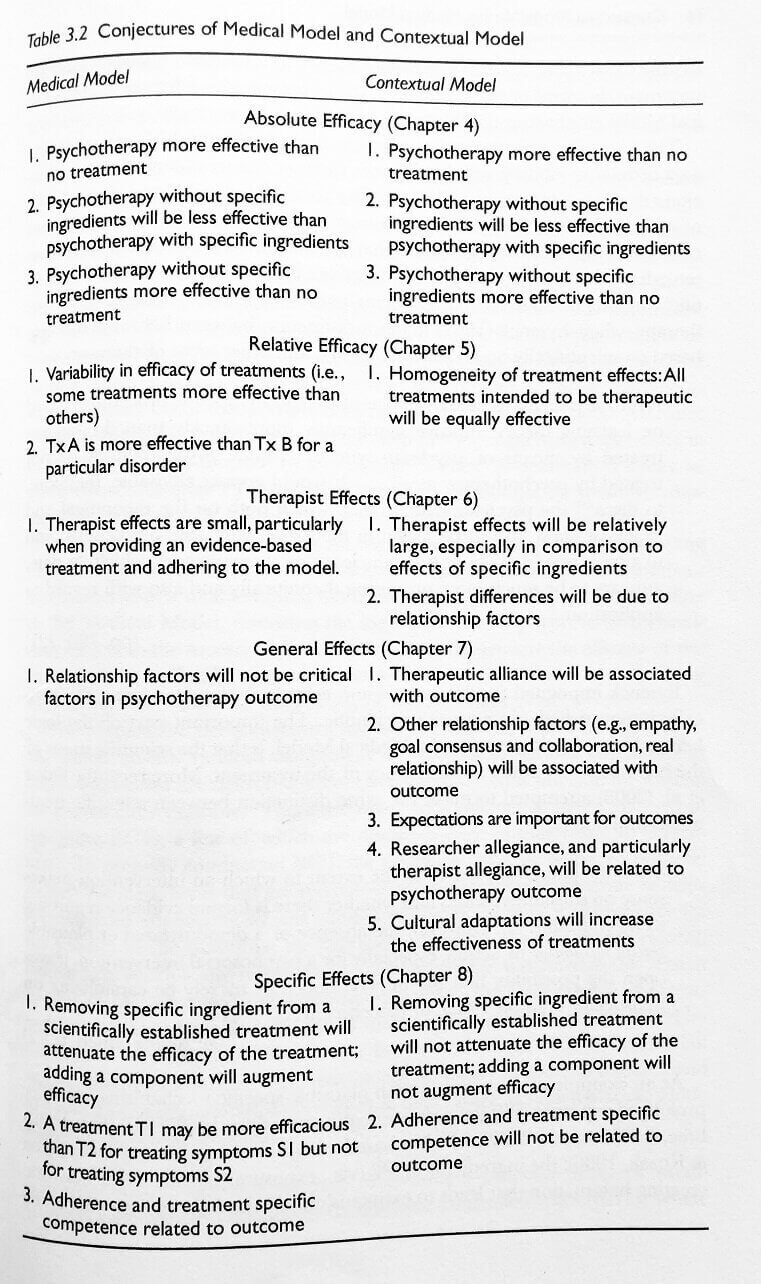

The Medical Model and The Contextual Model are two different research programmes which make very close predictions. But there are specific ways the hypotheses can be teased apart and tested and I think The Contextual Model is the more progressive programme. Here is the table from The Great Psychotherapy Debate where Wampold lays out the conjectures of each programme:

These are a list of conjectures that each research programme makes in order to predict and interpret data on the practice of psychotherapy and the results of psychotherapy outcomes research. Notice the predictions for "absolute efficacy" are identical in both models. The models diverge from there in examinations of "relative efficacy," "therapist effects," "general effects," and "specific effects."

Last year I spoke to one of my professors who was the director of the MFT program at CSULB which I attended. She's a trauma researcher and allied to The Medical Model. In our conversation about what works in treatment, I was arguing for The Contextual Model, saying I believed "relationship factors" are more important than "specific ingredients." (Contextual Model 6.1-6.2)

She argued that treatment for post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) proved that The Medical Model was correct, saying , "I've had many patients come into treatment with me who had a great relationship with their previous therapist but their PTSD symptoms had not gone away. But upon doing prolonged exposure treatment in my clinic, their symptoms went away." Her claim was that a specific ingredient (prolonged exposure) is necessary for the effective treatment of PTSD. (Medical Model 8.1)

Both models predict that some sort of specific ingredient is necessary (Medical Model 4.2, Contextual Model 4.2). So what is the difference between what they’re claiming?

The Medical Model claims that specific ingredients target specific symptoms and therefore, adherence to a specific manual for treatment will be associated with outcome (Medical Model 8.1, 8.3). The Contextual Model claims you need a number of things to get a positive outcome: 1. A relationship 2. An adaptive rationale for the problem which is accepted by patient and therapist which provides hope and expectancy for change 3. A ritual which the patient and therapist perform into which effort is exerted. It’s claim is therefore that you need a clear explanation and ritual but the removal of a particular specific ingredient will not be associated with outcome. (Contextual Model 8.1-8.2)

That is to say - Dr Ghafoori was right to say that the strong relationship is not enough. Both models predict that a relationship without a clearly defined rationale for treatment and a ritual to be performed for treatment will be insufficient.

But her interpretation of The Medical Model would predict that any treatment lacking in exposure would not alleviate PTSD symptoms. The hypothesis she implied is directly out of The Medical Model: competence with and adherence to a treatment manual involving exposure will predict outcomes (Medical Model 8.3). Alternatively, The Contextual Model’s hypothesis is that a ritual that is accepted by the client and therapist must be performed (Contextual Model 4.2) but it will be therapeutic alliance, relationship factors, expectations, allegiance to the treatment, and culturally appropriate adaptations which predict outcomes (Contextual Model 7.1, 7.2, 7.3, 7.4, 7.5).

III

How can we test this? Well, first we can look at what The Medical Model says about PTSD. The medical model predicts there are specific ingredients that are required for successful symptom reduction: 1. targeting triggering stimulus through exposure to extinguish the affective response 2. targeting negative thoughts and beliefs that arise after the traumatic event through cognitive restructuring.

A treatment for PTSD was developed with neither of these specific ingredients. This treatment was called Present Centered Therapy and was developed initially as a pseudo-placebo control that had a cogent rationale (adaptive explanation) and therapeutic actions (a ritual). A 2014 meta analysis determined this treatments effectiveness was similar to previously established Evidence Based Treatments for PTSD such as Prolonged Exposure.

The effectiveness of a treatment without the specific ingredients hypothesized as necessary by The Medical Model directly contradicts it's prediction (Medical Model 8.2, 8.3)

So now we have to ask if the predictions of The Contextual Model (Contextual Model 7.1, 7.2, 7.3, 7.4, 7.5) do a better job.

Is therapeutic alliance associated with outcome? (Contextual Model 7.1)

Yes: “In sum, the overall relation between alliance and outcome in individual psychotherapy is robust, not effected by the file drawer problem, and accounts for approximately 7.5% of the variance in treatment outcomes.” (Horvath et al. 2011)

Are relationship factors associated with outcome? (Contextual Model 7.2)

Yes: The APA’s task force on Evidence-Based Relationships and Responsiveness considers collaborative relationships including goal consensus, empathy, feedback, and a positive regard as a demonstrably effective in enhancing psychotherapy outcomes. (APA 2019)

Are expectations important for outcomes? (Contextual Model 7.3)

Everyone seems to cite neuroscientist Fabrizio Benedetti on this. The most relevant quote I could find from him seems to suggest that yes, they are important: “Hidden administration of therapies has provided compelling evidence that expectation is a key element in therapeutic outcome (Benedetti et al., 2011c, Colloca et al., 2004). If the patient is unaware that a treatment is being performed and has no expectations about any clinical improvement, the therapy is not as efficacious. This has profound implications in terms of medical practice because the information delivered by health professionals can impact therapeutic outcome.” (Benedetti 2013)

Is researcher allegiance related to psychotherapy outcomes? (Contextual Model 7.4)

Yes: “Researcher allegiance (RA)-outcome association was robust across several moderating variables including characteristics of treatment, population, and the type of RA assessment. Allegiance towards the RA bias hypothesis moderated the RA-outcome association. The findings of this meta-meta-analysis suggest that the RA-outcome association is substantial and robust.” (Munder et al. 2013)

Are culturally adapted treatments more effective? (Contextual Model 7.5)

Yes: “The results provide evidence that culturally adapted psychotherapy produces superior outcomes for ethnic and racial minority clients over conventional psychotherapy by d = 0.32. The outcome differences favoring culturally adapted treatment were moderated solely by cultural adaptations of illness myth” (Benish et al. 2011)

IV

The Medical Model and The Contextual Model are competing research programmes. Presently, The Medical Model is the dominant research programme or, in Kuhn’s terms, the “normal science” of our field. The researchers within The Medical Model have been developing Evidence Based Treatments (EBTs) that contain specific ingredients to target specific symptoms for decades. But our outcomes are stagnant. Despite the efforts to develop EBTs, psychotherapy hasn’t improved in its ability to help people since we began measuring its effectiveness in helping people in the 70s. Since the project to develop specific treatments to remediate the symptoms of psychological disorders hasn’t borne out the promise of better outcomes in treatment, The Medical Model is a degenerative research programme.

The Contextual Model makes a number of predictions about what accounts for outcomes in psychotherapy. There’s an enormous amount of variation in the quality of scientific evidence but I believe the meta analyses and expert reviews I’ve linked here are high quality. The predictions of the contextual model have been borne out in the data. Taking the Lakatosian view, I believe the accuracy in the explanations and predictions of The Contextual Model make it the more progressive research programme. The Contextual Model is still a minority voice but I predict that over the next 10 years, The Contextual Model will gain adherents more rapidly than The Medical Model.

The Great Psychotherapy Debate has taken me about a year to get through. I haven’t been able to digest all the parts of The Contextual Model. I feel uneasy in regards to what it suggests about the role that specific ingredients play in psychotherapy. But perhaps my concerns there are tangent to what The Contextual Model actually says. The aim of The Contextual Model is to change our focus so that we can more reliably improve outcomes in psychotherapy. I’m on this ride so let’s see where this paradigm shift takes us.