Blog

If Psychoanalysts Care So Much About the Truth of the Unconscious, Why Aren’t They Obsessed with Behavioral Economics?

Psychoanalysts have long styled themselves as truth-seekers: explorers of the hidden motives, infantile fantasies, and disavowed desires that govern human behavior beneath the surface of conscious awareness. Their vocabulary, “interpretation,” “insight,” “the return of the repressed,” rests on an epistemic claim: that psychoanalysis is a method for discovering truths obscured by defenses, not merely a form of storytelling or consolation.

It is a field preoccupied with the question of why people do what they do. Psychoanalysis’ central premise is that human action is not transparent to itself; that confession, intention, and rationalization conceal deeper forces": drives, identifications, archaic object relations.

From Freud’s dream interpretations to Lacan’s insistence that “the unconscious is structured like a language,” the analytic tradition treats the mind as a theater of concealed motives. A patient says one thing but means another. A slip of the tongue reveals the hidden wish. The analyst listens for the latent beneath the manifest.

The American Journal of Psychoanalysis in its December 2023 issue it clear: “the pursuit of truth is a central aim of psychoanalysis.”

Meanwhile, in the last half century, another field has quietly conducted thousands of experiments designed to measure unconscious motivation rather than merely infer it through interpretation. Behavioral economics, emerging from the work of Daniel Kahneman, Amos Tversky, Richard Thaler, and later popularized by writers like Dan Ariely and Robin Hanson, has empirically mapped the predictable irrationalities that shape decision-making.

Hanson and Kevin Simler’s The Elephant in the Brain is an extended argument that from charity to religion to politic, much of human behavior is driven by self-interest and signaling; motives we prefer not to acknowledge. In other words, it’s a modern, data-driven account of the unconscious; one that replaces free association with controlled experiments, and transference with incentive structures.

Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow describes conflicts within the brain between different systems. “System 1” is fast, intuitive, unconscious cognition which routinely subverts “System 2” which does planning and deliberative reasoning. Behavioral economists have cataloged dozens of biases (confirmation bias, loss aversion, hyperbolic discounting) that distort self-perception and decision-making in ways individuals are completely unaware of.

This is, in essence, a rigorous empirical study of the unconscious, precisely the domain psychoanalysis claims as its own.

And yet, psychoanalysts rarely engage with this literature. The analytic journals that once obsessed over unconscious motivation now largely ignore the vast empirical body that demonstrates in measurable, replicable ways that unconscious processes shape judgment and choice.

Where are the psychoanalytic commentaries on Kahneman’s biases? On Ariely’s deception studies? On the signaling models that reveal how altruism, mate selection, and moral outrage serve hidden functions? The overlap is enormous. The shared object of study, the mind’s tendency to conceal its own motives, is unmistakable.

If Freud were alive today, it’s hard to imagine him not being fascinated by the experimental proof that humans routinely deceive themselves. But the analytic establishment seems oddly uninterested… as though empirical confirmation of their deepest premise would somehow cheapen it.

The disconnect is glaring. Behavioral economics has, in many ways, realized the psychoanalytic dream: a systematic, reproducible exploration of the unseen forces that govern human behavior. Yet psychoanalysis, still proclaiming itself the science of the unconscious, barely looks up from its own canon.

If psychoanalysts truly care about truth, about exposing the motives that govern us outside awareness, they should be thrilled by the rise of behavioral economics. Here, finally, is a field that operationalizes the unconscious, measures its effects, and invites cross-disciplinary synthesis.

Instead, psychoanalysis risks repeating its own historical pattern: defending its methods rather than expanding its reach. A field that once prided itself on radical insight now risks being left behind by the very inquiry it inspired.

As seekers of the truth, we should be integrating psychoanalysis with behavioral economics. We shouldn’t lay dormant, accepting Popper’s claim that Psychoanalysis is a pseudoscience. We should be testing our models, updating them in light of current information, and using that knowledge to help our clients uncover truths about their own lives.

The List of Defense Mechanisms

Defense mechanisms are your mind’s automatic safety features. When an experience, thought, or feeling threatens to overwhelm you—like a sudden blinding glare while you’re driving—these mental reflexes flick on in the background. They dim the emotional brightness just enough to keep you steady so you can stay on the road of daily life. Most of the time the switch is flipped without your even noticing…

Defense mechanisms are your mind’s automatic safety features. When an experience, thought, or feeling threatens to overwhelm you—like a sudden blinding glare while you’re driving—these mental reflexes flick on in the background. They dim the emotional brightness just enough to keep you steady so you can stay on the road of daily life. Most of the time the switch is flipped without your even noticing; you simply find yourself cracking a joke, changing the subject, or picturing a happier outcome. Those moves are your psyche’s way of protecting you from an emotional overload.

Nancy McWilliams is an American clinical psychologist and psychoanalyst. Over decades of teaching, supervising, and writing—most famously in her book Psychoanalytic Diagnosis—she has become one of the clearest translators of complex psychodynamic ideas for therapists and students around the world. Colleagues often turn to her work because it blends deep scholarship with plain-spoken examples and genuine compassion for real people’s struggles.

McWilliams arranges defense mechanisms on a kind of developmental ladder. At the bottom are the earliest, bluntest tactics toddlers and very distressed adults may use—total denial of a problem or imagining they have magical control over everything. In the middle are the everyday coping styles most of us recognize, like shifting our irritation from the boss to the dog or burying a painful memory until we can face it later. At the top are the mature maneuvers—humor, forward planning, helping others—that let us acknowledge reality while managing our feelings gracefully. Everyone uses a mix from every step; what matters is which rung you stand on most of the time and whether you can climb to a higher one when life turns up the heat.

Clinically, McWilliams cautions that the usefulness or danger of any given defense hinges on two things: the person’s overall level of personality integration and the immediate context. A retreat that is restorative one day could be a psychotic break the next; what matters is flexibility, reality testing, and whether the person can shift to more mature options when stressed.

McWilliams lays out the defenses on a three-tier developmental ladder: primary or “primitive” defenses (typical when reality testing is shaky, as in psychotic, borderline, or very fragile narcissistic personality structures), secondary or neurotic-level defenses (the everyday coping styles of the classic hysteric, obsessive, or depressive profiles), and mature or high-adaptive defenses (strategies that protect feeling while leaving reality intact, like humor, anticipation, and sublimation). She stresses that everyone uses defenses from every tier, but clinical attention goes to which stratum predominates, how flexibly a person can shift upward under stress, and whether the same maneuver is adaptive or risky in its context. With that map in mind, here is the roster of defenses, moving from the earliest and most reality-distorting to the most reality-embracing.

Primary / “Primitive” Defensive Processes

Autistic (schizoid) withdrawal / fantasy - Retreat into an inner world that feels safer than outer reality.

Denial - Erase a piece of external or internal reality as if it does not exist.

Omnipotent control - Act or fantasise as though one’s wishes can magically dictate reality.

Primitive idealisation & devaluation - Split perceptions of self/other into “all-good” or “all-bad,” with sudden flips.

Projection - Disown an impulse or affect and attribute it to someone else.

Projective identification - Evoke, coerce, or “recruit” the disowned feeling in the other person.

Splitting - Keep contradictory self- or object representations apart, preventing integration.

Dissociation - Automatic detachment of experience from awareness (up to psychotic levels).

Acting-out - Discharge conflict by behaviour rather than symbolisation or awareness.

Somatization - Convert conflict or affect into bodily symptoms.

Secondary / “Neurotic-Level” Defenses

Repression - Keep an idea, memory, or affect out of consciousness.

Regression - Retreat to an earlier developmental mode of thinking or relating.

Isolation of affect / compartmentalisation - Separate ideas from the feelings attached to them.

Intellectualisation - Replace feeling with abstract, excessively cognitive rumination.

Rationalisation - Invent plausible but self-serving explanations for motives or actions.

Displacement - Shift an impulse from an unsafe target to a safer one.

Reaction formation - Transform an unacceptable impulse into its opposite.

Reversal (turning against self / passive-into-active) - Change who is active or passive, giver or receiver, in a conflict.

Undoing - Perform an action meant to magically cancel out or atone for another.

Sexualisation - Endow an issue with erotic meaning to gain distance from its real impact.

Mature / “High-Adaptive” Defenses

Anticipation - Experience future discomfort in fantasy in order to prepare for it realistically.

Suppression - Consciously defer an impulse or thought without repressing it.

Humor - Point to the incongruous aspects of a conflict, sharing the joke with others.

Sublimation - Channel the energy of an unacceptable impulse into a socially valued aim.

Altruism - Derive gratification from meeting other people’s needs.

Affiliation - Turn to others for help or support rather than distorting the issue internally.

Self-assertion - Directly express thoughts and needs without aggression or manipulation.

Self-observation - Reflect on—and sometimes gently laugh at—one’s own motives and behaviour.

Asceticism - Manage conflict by voluntarily renouncing pleasurable experiences.

Task-orientation - Convert affective turmoil into constructive problem-solving activity.

Think of this catalogue less as a moral scorecard and more as a weather report on your inner climate. Everybody will dip into the “primitive” or “neurotic” zones under heavy stress; what distinguishes psychological health is flexibility—the capacity to notice what you are doing, reality-check the situation, and reach for a higher-rung option when you’re ready. That act of naming turns an unconscious shield into information you can think about and, if you wish, revise. The “developmental ladder” model reminds us that dipping into “primitive” or “neurotic” territory is simply what minds do when they feel swamped; psychological health rests on flexibility: the capacity to notice where you are on the ladder, reality-check the situation, and reach for a higher-rung option when the heat dies down.

Growth starts with gentle curiosity rather than judgment: “What might this maneuver be protecting me from right now?” Pausing, breathing, and grounding your senses widens the window of tolerance so you can bear a bit more feeling without warping reality. From there you experiment with an incremental upgrade—moving, say, from denial to conscious suppression (“I’ll deal with it after lunch”) or from projection to self-observation (“Could that trait also be mine?”). Enlisting trusted friends, a partner, or a therapist to mirror back what they see accelerates the shift, and writing about or otherwise making meaning of the new experience begins to lock the higher-level defense in place. In conversation, the same principles apply: create safety with calm body language, own your process aloud (“I notice I’m getting defensive”), allow a brief silence so primitive impulses cool, validate whatever kernel of truth you can find, and keep explanations concise so they don’t morph into rationalization. If you discover you’re chronically stuck in rigid splitting, acting-out, or dissociation that harms work or relationships, treat that not as failure but as a signal that professional help could widen your coping bandwidth.

The single most crucial point is this: defenses are normal, automatic safety features—not flaws—and mental wellness hinges on how flexibly you can notice them and trade them up when circumstances allow. If you can catch yourself slipping into a blunt, reality-warping maneuver and consciously reach for a higher-rung alternative—even just one step up—you’re already converting unconscious reflex into deliberate, growth-minded coping.

Interview for "Unpopping" by Alex Benke: The Dodo Bird Verdict with Erik Anderson, LMFT

Read it here on the Unpopping Substack

How did you decide to become a therapist?

I hated this job I was working running Jiu Jitsu tournaments with a boss that was super corrupt and asking me to swindle people. I also knew I wasn’t good at concentrating while sitting at a desk. My therapist was encouraging me to be a firefighter or a police officer but I didn’t want to do those things so I asked her…

Read it here on the Unpopping Substack

How did you decide to become a therapist?

I hated this job I was working running Jiu Jitsu tournaments with a boss that was super corrupt and asking me to swindle people. I also knew I wasn’t good at concentrating while sitting at a desk. My therapist was encouraging me to be a firefighter or a police officer but I didn’t want to do those things so I asked her, “can I do what you do?” She said, “well, you don’t have a personality disorder so I don’t see why not.”

I decided I just really wanted to see clients because it would keep my attention to sit down in front of someone instead of sitting in front of a computer and struggling not to browse reddit.

There’s this trend online where, when faced with a really tough question or issue, people encourage others to “see a therapist” in the same way they might say “see a doctor” when you’ve got a physical issue. People seem to say this thinking there’s “good therapists” and “bad therapists” which really must just depend on the therapist’s personality like whether they are “validating” by believing and listening to you or whether they are dismissive.

I, as a therapist, get frustrated when people online in places like r/relationshipadvice and people say “you shouldn’t be asking strangers online – you need to see a therapist.” I often think, “what the fuck am I going to tell you?” They’re asking for advice and it’s not like I’m some superhero who has completely new ideas that other people couldn’t have.

It’s not the same thing as reading an X-Ray where there’s a doctor who can help you read an X-Ray when lay people usually can’t. It’s like, “this is my life – can you read this for me and tell me what to do?”

Yeah, I’m not sure people are right to believe therapists have special skills that others don’t have or a specialized approach that lay people can’t comment on.

What did you think therapy was when you started studying it in school?

I went in to grad school thinking there were certain things I have to study that are right. I thought I was going to read the DSM and learn what the diagnoses are. I thought I was going to be able to listen to what my professors said and just know how to solve people’s problems. My therapist was really helpful with my negative thoughts and beliefs about myself and my relationships. She would help me identify automatic negative thoughts, identify cognitive distortions and challenge them which seemed to be the right answers for what I was experiencing then. I believed those were the right answers that would help me and it seemed like my therapist knew things I didn’t and could see things which I didn’t.

It felt like therapy had the right answers when my depression or whatever mental health disorder I had caused me to have the wrong answers. It seemed like therapy had a method that helped and you had to stick to the method like my therapist did.

When I was in school my professors taught me that different styles of therapy had different levels of effectiveness and I believed that. They treated the idea that different styles of therapy could be just as effective as one another as ridiculous. One of my professors did research on how specific ingredients in trauma therapy would lead to different outcomes. I studied the stuff on what my professors gave me – a lot of them were manuals for how to do a style of treatment. That’s what I thought therapy was when I started: you were going to help people with these methods and they would get better as they learned how to relate differently to their minds so they didn’t have these problems. I was sure therapy would help them get over their diagnoses whether it was cognitive behavioral therapy for depression, prolonged exposure therapy for trauma, or exposure and response prevention for obsessive compulsive disorder.

When I started working I was different than my supervisors – they liked depth psychology and Carl Jung and were somewhat psychoanalytic. In a supervision group a guy I was working there with said he heard a podcast on outcomes in psychotherapy that he thought I would find interesting. They talked about this book about the evidence on what makes therapy work and I immediately bought it and read it. I read this book called The Heart and Soul of Change which reviewed research and evidence, going over what we knew and how we knew it and it had these really vague results about what works that I had a hard time with. I thought you just had to stick to a particular method and this book completely contradicted that.

For the last 40 years there’s been a lot of new styles of therapy developed: EMDR, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Internal Family Systems… all of these are styles that get these manuals written about them where it seems you have to just do it right. They all brag that the evidence shows they’re Evidence Based Therapies. The Heart and Soul of Change said that whole body of research suggested they were misled and that there were other things that determined the effectiveness of therapy that varied a lot from therapist to therapist and that those differences had a lot more to do with outcomes than how closely therapists were sticking to the manual.

I experienced this profound doubt about what I was doing… I didn’t like the idea of therapists being these vague healer figures doing this process of change that is not well defined.

It made me feel like a priest doing something ridiculous and woo rather than a clinician delivering an empirically supported treatment, which is what I thought I was. I went into my sessions after that experiencing so much doubt that my clients could all see it and I lost about 50-60% of the people I was working with over the course of a couple months. I had to rebuild from that place.

So you went into psychology determined to laser in on the right way to do therapy as supported by science—the research-backed formulas behind the therapy that actually work. But then you stumbled upon the Dodo Bird Verdict. Can you tell me in layman’s terms what that is?

So the Dodo Bird Verdict is a finding that has been replicated many times in research on outcomes in psychotherapy over the last hundred years (since it was first found in 1928). It’s the finding that all forms of therapy that contain things that seem to make them things we’d actually call therapy, whether this is psychodynamic, humanistic, cognitive behavioral, or something new all seem to have similar outcomes. They are all similarly helpful and similarly effective when we study how they work for many different conditions.

That is to say, the style you use makes almost no difference in whether people get better from therapy or not.

So for those that reject this research – on what terms do they reject it?

Therapists go to a lot of trainings for new styles of therapy. If you go to a training on Emotionally Focused Couples Therapy they will talk to no end about the research showing it’s more effective than other couples therapies and they’ll point to studies that show that. But the problem with those studies is they’re typically conducted by researchers who are invested in Emotionally Focused Couples Therapy or therapists who believe it is better than other styles.

People who reject the Dodo Bird Verdict are often only vaguely aware of what it is and how big the body of research supporting it is. They say things like, “oh, I know that, we all know that the relationship is the most important thing in therapy.” But then they still point to those studies showing some therapies have better outcomes than others while never having looked into how much bias impacts those studies.

They aren’t willing to accept all of its conclusions often because they so repeatedly hear the claim that some styles are newer and more effective, which for a while insurance companies played into. But recently even insurance companies have started taking a different approach and looking at outcome measures rather than styles used.

So how did this end up affecting your practice?

I had been sure that learning more about the right evidence based treatments was the right thing but now I was seeing the whole evidence based treatments model as flawed. I completely questioned what I was doing and what could make me a good therapist. I didn’t want to be a priest blessing people with holy water and telling them they’re getting better. It was disturbing to me as someone who wanted the right answers.

Most therapists I talked to were fine with this and would say, “we always knew therapy was about the relationship,” reflecting a vague understanding of the research while accepting that they’re some sort of healers.

The thing that got me back on track was reading more about the things effective therapists do need to do.

So what do effective therapists need to do?

Researchers find that there are some things within the therapist’s control which help people get better in therapy and most of it is about how good the therapist is at building a working relationship with the client.

A working relationship has to do with whether they make the client feel heard, understood and respected; whether they understand and agree with the client about what their goals are; and whether they’re able to use their approach in a way that helps their client make sense of their problem, clarify how they can work on their problem, and where they need to be putting effort in on their problem. Those descriptions are purposely vague because we’ve found many different therapies, even ones that seem pretty alien to one another, seem to be equivalently helpful for people trying to overcome their problems or reducing their symptoms.

How did this impact your perspective of your goals/your vision for your career/therapy in general?

I worked on trying to give my clients explanations and rationale for how they could change and trying to better instill hope and expectancy that they could change. I tried to clarify what they could do to change and how we would work on it. You work along with them but it’s also on them at this point whether they do put in effort to change their problem. The funny thing along the way is that you actually do need a therapeutic style to deliver those things but the particulars of the style doesn’t matter that much. It could be a psychodynamic style, emotionally focused style, internal family systems…

I discovered I could deliver therapy in the styles that had been helpful to me. This felt like a way to be genuine and honest with people while helping them figure out their problems. But I also decided to start measuring whether people were getting better in my care because I realized that as long as people were getting better in my care I could feel good about what I was doing.

It took a lot of work for me to feel confident delivering therapy. I felt like I had to understand what I was doing. I now understand therapy to be a process of an all too human healing ritual. Medicine doesn’t totally understand why people get better from healing rituals. In medicine when people get better without the active ingredient doing it, we call that the placebo effect. And the researchers I was reading suggested that therapy specifically targets what medicine rejects as “the placebo effect” that we might otherwise call “the internal process of healing and change.”

The research on the placebo effect shows it has large effects on pain, anxiety and immune function. Therapy seems to help people suffer less, experience less anxiety, function better in measurable ways including incurring lower medical expenses over their lifetime…

…same as placebos.

Yes, but we also know the placebo effect varies a lot from doctor to doctor the same way treatment effectiveness varies from therapist to therapist. In fact, psychiatrists prescribing the same medication will have three times as good outcomes as other psychiatrists depending how good their “bedside manner” is.

So is all you do a placebo?

I think were you to phrase it that way, it’s like saying “so Yoga is just really hard stretching?” It’s using specific language that accurately describes what something does while also rejecting it. In philosophy it’s sometimes called Russell Conjugation when you say something like, “I stand up for myself, you won’t take no for an answer, she always needs to get her way.”

Therapy is something that activates the internal human capacity for healing and change that can turn on in social settings.

Humans seem to be able to heal and change from many conditions when given the right social conditions with healer figures. I had a hard time overcoming seeing this as odd or woo but we know that this method is one of the ways people overcome mental health conditions. Therapy seems to help people suffer less, be less sick, and have overall more wellbeing. It’s an effective treatment with a lot of evidence showing people get better from it.

I like to rephrase “therapy is just the placebo effect,” to, “therapy is a process that activates a human’s internal process for healing and change.”

Are there any misconceptions about psychology/therapy that you see on social media that particularly drive you insane? And can you give us the facts of those fictions?

Typically the depiction of therapists having all the answers about, “if you’re experiencing this that is because of that.” Like, “if you feel jumpy, that’s a trauma response…” “if you have rejection sensitivity that’s because you have ADHD.” Really? The things we know have clear relationships are usually things in the DSM. But the DSM doesn’t say much about what causes mental health disorders in the brain. Really, we don’t know what mental health conditions are but we know there seem to be certain clusters of symptoms we call and categorize as ‘disorders.’

When therapists get on social media and talk about the things they believe come along with ADHD or the reasons from your past you feel this or that way. When therapists start naming things to look for it can sometimes get dangerous because they may be making truth claims about things that just aren’t well established. One of the ways we’ve seen this go really wrong was in the 80s when therapists were very vocal about many symptoms of discomfort being related to repressed memories. There are people still suffering the effects of being sentenced to jailtime, admitting to atrocities they didn’t commit or disowning their family because of believing in repressed memories.

Most therapists believe they can’t be harmful as long as they’re just trying to be helpful and it just isn’t the case. We know there have been some harmful therapies such as rebirthing therapy where children were smothered to death under blankets. But most harmful therapies are more subtle through teaching clients or the public harmful false beliefs.

In part, I see my role in therapy as being my client’s personal philosopher. I’m trying to help them form a more true or realistic understanding of their life, what they can do to make their life better, and how to make good moral decisions.

I very rarely use the terms “healthy and unhealthy” because I think they’re so overused in popular psychology. I was surprised I used “healthy” the other day in talking to a client but here’s an example of a rare exception where I will use it. A client said he thought he had a masturbation addiction because he told himself and his partners he would never do it. He was also not having premarital sex so he had no outlet for sexual energy. When he inevitably would masturbate he would feel profound shame and guilt and it made him feel other symptoms like difficulty focusing and fatigue. I stated that when we look at studies of human sexuality it appears across cultures, genders and ages and thus we think of it as normal and healthy. That’s one of the few instances where I’ll say something like that. I see many other therapists going much further than that with their statements of what healthy and unhealthy are and I think those are philosophical statements that therapists are typically unjustified in making.

Where can people find out more about you?

Please check out my website.

And if you’re interested in reading what I’ve written about what makes therapy work, check out my blog series on the topic starting here.

8 Defense Mechanisms and How to Overcome Them

Everyone is guilty of being defensive at times. But what does it mean to be defensive, really?

Sigmund Freud coined the phrase defense mechanisms while his daughter, Anna Freud, went on to elaborate on the concept. The way we think of defense mechanisms has changed somewhat since these early writings, but simply put, defense mechanisms are largely-unconscious psychological habits we use to protect ourselves…

Everyone is guilty of being defensive at times. But what does it mean to be defensive, really?

Sigmund Freud coined the phrase defense mechanisms while his daughter, Anna Freud, went on to elaborate on the concept. The way we think of defense mechanisms has changed somewhat since these early writings, but simply put, defense mechanisms are largely-unconscious psychological habits we use to protect ourselves from feeling fear, shame, or sadness.

Put differently, psychodynamic defense mechanisms are inner tools that our minds use in an effort to cope with difficult feelings. When we experience a stressful event or interaction that threatens our sense of security, our psyches look for ways to defend itself.

Being able to protect ourselves from potential emotional injury during extremely stressful events is an important element of resilience; but sometimes, we come to rely too heavily on certain defense mechanisms, and as a result, we grow increasingly fragile and our relationships suffer.

So how can we navigate an often emotionally-dangerous world without becoming fragile? How can we be genuinely resilient in the face of challenging situations and conflicts, instead of becoming defensive?

In this blog post we will discuss 8 defense mechanisms that are especially common, and how to overcome defensiveness. Spoiler alert: the first step to being less defensive is to learn more about the different shapes your defensiveness may take—so read on!

Denial

The first psychodynamic defense mechanism on our list is denial. Everyone knows what denial is, and that it can make hard situations even harder. When we deny that something stressful has happened or is happening, we’re usually preventing ourselves from dealing with the problem.

If you’re thinking about times in your life when you were in denial of a particular situation, don’t be too hard on yourself. In retrospect, it might be easy to recognize how denial might’ve exacerbated a rough situation. But, the reason denial is so overwhelmingly common is that it really works—to relieve pain, that is. When we can even superficially convince ourselves that something terrifying or tragic isn’t happening, our suffering drops. And as humans, we are hardwired to love things that lessen our suffering in the short-term.

The good news is that, even though our brains may love denial, we don’t have to stay stuck in this habit forever, especially as it pertains to your day-to-day life.

Displacement

People who use displacement to cope with life tend to take their negative feelings about one person out on an entirely different, usually innocent, person. A person who’s furious with their boss, for example, might come home and take their anger out on a family member.

Like all defenses, displacement feels good to us in the moment—it allows us to express our anger (or other unpleasant feelings) and feel in control. By dumping our emotions on someone who doesn’t scare us, we get to feel big and powerful. Or, put differently, we get to escape our feelings of vulnerability and fear. The problem of course is that after that initial surge of satisfaction, we’re left feeling remorseful and ashamed of our actions.

And, there’s probably a very real benefit to displacement, in the moment—in the above example, the person who’s taking their rage out at home has successfully avoided blowing up at work, which could have serious financial consequences for the whole family.

Of course, displacement is almost never helpful—even in short-term, stressful situations. Displacing that anger into another relationship may save your job, but you’ll be harming that relationship. And, without any anger management tools, it’s likely to be unsustainable—you’re bound to eventually lose control of when and where you vent your feelings.

Of all the psychodynamic defense mechanisms, displacement may be one of the hardest for not only the defensive person—who’s likely struggling with shame and insecurity—but on family members and friends.

If this description sounds familiar, that’s great news—it means you’re willing to start recognizing this destructive pattern, which is an important first step.

Dissociation

Of the 8 defense mechanisms discussed in this blog post, dissociation might be the most inconspicuous, especially to those around you. Dissociation describes a sort of mental “checking out” that lets us bail out of unpleasant situations by going numb or detaching ourselves from the present.

If you consider yourself a daydreamer, don’t worry—not all dissociation is harmful or indicative of trauma. Humans naturally dissociate, or “zone out,” to cope with unpleasant feelings like boredom and frustration. This type of adaptive dissociation can help our brains save energy so we can better focus later on.

As with other psychodynamic defense mechanisms, dissociation can be quite adaptive in extremely stressful situations. For example—if a parent loses their spouse in a sudden accident, they may dissociate in the immediate aftermath so they can effectively take care of their children. In this case, dissociation would be protecting this parent from falling apart to such a degree that their children would be harmed by neglect, and they themselves would be additionally harmed by their own guilt.

Dissociation is maladaptive, or harmful, when we use it so much that it gets in the way of solving a problem that is in fact solvable. An example of this would be if a person was in an abusive relationship. They may be aware that the relationship is abusive (or, in other words, not in denial), but so dissociated from any feelings of anxiety or urgency that they remain in their unsafe environment.

Intellectualization

Imagine that a surgeon is conducting an operation, and an unexpected emergency arises. Would you want that surgeon to react by feeling the full weight of terror triggered by the potential of losing their patient? Or would you want them to remain firmly in control, capable of making swift, precise decisions?

The above hypothetical scenario is of course an example of how intellectualizing can be extremely helpful. There are certainly times when shutting down emotionally and redirecting our energy into logic, reasoning, and planning, is essential.

However, relying too heavily on this psychodynamic defense mechanism is a recipe for unhappiness.

Feelings are guideposts that allow us to make sense of life and all that has happened. Emotions are information we need in order to protect ourselves, remove ourselves from harmful situations, and intuitively “read” people and events. Emotions are also what allow us to feel deeply connected to others, and to feel fully alive in the present moment.

Projection

The term projection gets thrown around, but as one of the psychodynamic defense mechanisms it means that someone has a feeling or reaction that they do not want to feel or experience, or recognize in themself. The act of projection occurs when that feeling or attribute that we don’t like gets placed onto another person.

Let’s say a person seems to frequently comment about a friend of his who’s gained a little weight recently. The friend knows this about himself, but doesn’t mind too much—he’s been busy with a big project at work, and knows he’ll get back to the gym soon. But his friend just can’t let it go. Every time he’s in the company of their mutual friends, he can’t stop himself from making comments like, “I just can’t believe how he’s letting himself go,” and, “he must be depressed about it and just too ashamed to admit it.” Their mutual friends all suspect the same thing: his apparent inability to stop talking about his friend’s weight may indicate that he himself is feeling insecure about his own appearance.

We’re all familiar with scenarios like this one. And, if we’re lucky, we’ve been able to recognize when we’ve been guilty of projection ourselves—times we’ve been critical of others for traits we’re unhappy with in ourselves or situations we’re scared to face.

In the short-term, projection does a great job providing relief from shame and fear. Our external focus—on someone else’s personality or current life situation—is a great reprieve from the sometimes daunting task of looking inward and addressing our own issues.

However, that relief has a high cost. Similar to displacement, projection is almost never helpful, even during extreme circumstances. When used often, projection can warp our perspectives, making it harder and harder for us to see our own lives clearly and to meaningfully participate in relationships. If you’re guilty of projection and and curious about how to overcome defensiveness, you’ve already done the hardest part by acknowledging this behavior.

Reaction Formation

In Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Queen Gertrude describes an actor’s over-the-top performance as a wife declaring her loyalty by saying, The lady doth protest too much. Perhaps you’ve used this phrase—when, say, you’ve noticed a friend describing an attractive coworker. When you ask if they might have feelings for this coworker, they respond, “Oh my god, are you kidding? Ew, no! Never in a million years! I would NEVER date them! EVER!”

This example describes reaction formation, a psychodynamic defense mechanism in which a person demonstrates the opposite disposition that they actually feel. Another example would be if a person is going through a recent breakup, and emphatically tells all their friends how they’re doing absolutely fine, not missing their ex at all, and are purely excited to be single again.

In both of these examples, we can easily see the reason for reaction formation—having a crush and grieving a relationship are both intensely vulnerable states.

Importantly, reaction formation isn’t the same as simply lying. Rather, when we’re using reaction formation, we’re convincing ourselves that we do indeed feel these inauthentic emotions. The result, of course, is some short-term relief from our intense realities, and the long-term confusion of our own emotional experience. In other words, as with all of the 8 defense mechanisms, reaction formation may injure our emotional literacy over time, leaving us feeling alienated from ourselves.

Repression

You’ve probably heard the term repression before, but you may not know that it’s commonly confused with suppression, which describes the conscious, intentional “burying” of unwanted thoughts, feelings, or impulses. When we use repression, we’re silencing the unpleasant experience without any conscious effort.

The Freuds’ ideas about repression may be some of the more controversial among the psychodynamic defense mechanisms, and how we think of repression has evolved quite a bit over the decades. But, simply put, we use repression to alleviate us from desires that we worry could be problematic. Say for example that your building has a terrible landlord, who’s always coming by unannounced, making accusations, and neglecting repairs. It would be totally understandable to develop quite a bit of resentment—but you know that if you express any resentment, he’ll probably make your life even more miserable. Repression would allow you to get through all the conflicts without experiencing any of the resentment. You may even describe your landlord to others as merely, “a bit hard to communicate with sometimes.” Once you finally do move, you may find yourself hypervigilant and excessively guarded with your new landlord, almost as though you’ve developed some kind of phobia. You might be confused by your own reaction, since you thought you had handled your previous situation so well.

You may be noticing that repression is similar to denial. The key difference is that, whereas denial pertains to external circumstances, repression pertains to internal experiences. In the above example, you’re clearly aware of the actual circumstances—but you’ve repressed your resentment.

How to Overcome Defensiveness

If you’ve managed to read through these 8 defense mechanisms and identify some of your own defenses, congratulations—you’ve demonstrated the hardest part! After all, if you were completely defensive, this list would’ve simply made you say, “Oh I never do any of these things,” (repression!) or, “This is just like my friend, he is SO defensive…” (projection!).

We use psychodynamic defense mechanisms to avoid painful emotions like fear, shame, and self-loathing. That means that moving beyond defensiveness requires us to practice a tremendous amount of self-compassion. The first step in growing beyond maladaptive defenses is practicing identifying them. If we blame ourselves too harshly for being defensive, we’re destined to shut down. Instead, try thinking of your defenses as useful tools that have kept you safe, but that you’d like to set aside in favor of expanding your tool box.

Having a mindfulness practice that allows you to develop radical acceptance and self-compassion may be an excellent way to trade in your defensiveness for resilience. Once we’re able to believe that we’re good people who sometimes make mistakes, it becomes much easier to notice when we might be letting ourselves down by using unhelpful coping behaviors.

Consider Psychotherapy Today

Therapy can also be a great way to let go of the psychodynamic defense mechanisms holding you back. This is especially true if you struggle with anxiety and depression, which are very often exacerbated by defensive thought patterns.

In my practice, I use a humanistic perspective that empowers you to be the expert of your own experience. I’ve also found that some CBT practices can help clients learn how to consistently identify the painful thoughts they’re experiencing that are triggering their defenses. Sometimes, clients and I find that an old trauma is at the core of their defenses, and that a psychodynamic approach allows them to discover insight that leads to healing.

If you’d like to connect or set up a consultation, reach out at https://www.erikandersontherapy.com/contact. I work with clients across California, both in-person at my office in Mar Vista and online.

Psychedelic Assisted Therapy and Ketamine Assisted Psychotherapy

When I was a new therapist, the largest question on my mind was “how do I ensure I’m helping?” which often led me around to the question, “how does therapy work?” To answer these questions, I spent a lot of time with textbooks such as The Heart and Soul of Change, and The Great Psychotherapy Debate (which I wrote about in a blog here). This exploration eventually led me to seminars and trainings with Scott D Miller, one of the preeminent experts on Outcomes in Psychotherapy. I have been measuring outcomes in my private practice…

When I was a new therapist the biggest questions on my mind were, “how do I ensure I’m helping?” and, “how does therapy work?” I spent a lot of time with textbooks such as The Heart and Soul of Change, and The Great Psychotherapy Debate (which I wrote about in a blog here). This exploration eventually led me to seminars and trainings with Scott D Miller, one of the preeminent experts on Outcomes in Psychotherapy. Since then I have been measuring outcomes in my private practice and routinely collecting feedback in my work using MyOutcomes software in a process known as Feedback Informed Treatment.

After addressing those questions, I’m still asking “how do I better help people?” Scott D Miller and others such as Daryl Chow answer that by telling us to engage in Deliberate Practice - which I think is a pretty good answer! But I think there is also another program in therapy where we are developing practices that dramatically improve the standard of care in therapy: Psychedelic Assisted Therapy, which includes treatments like Psilocybin Assisted Therapy and Ketamine Assisted Psychotherapy (KAP).

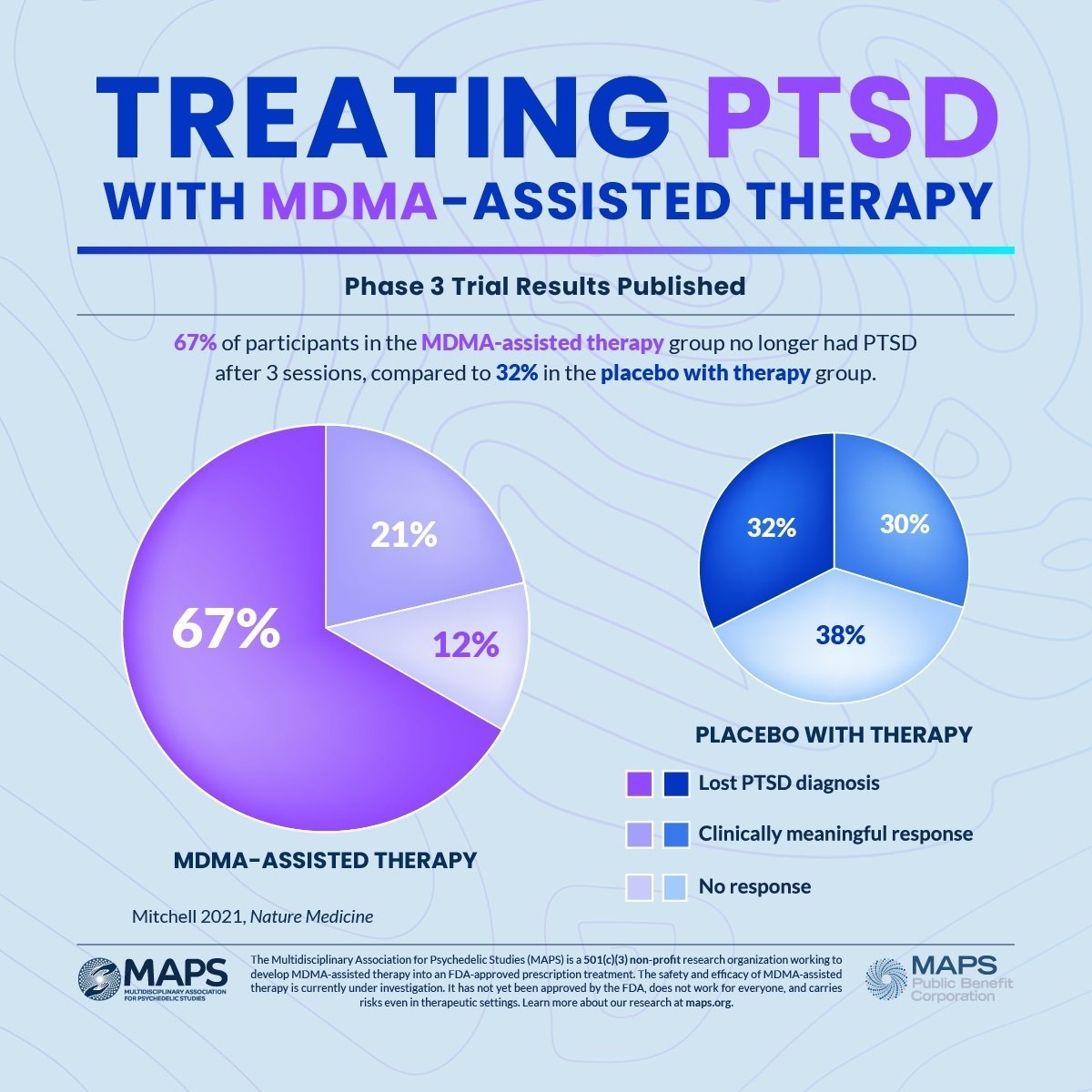

I first heard about Psychedelic Assisted Therapy in the early 2000s when I read exciting posts on the internet describing the work coming out from Johns Hopkins University looking at how Psilocybin (magic mushrooms) affected people. They were reporting on research about the positive effects of mystical experiences occasioned by the administration of high doses of Psilocybin, but later they were researching its mental health benefits such as how “Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer.” In addition to universities researching Psilocybin Assisted Therapy, nonprofits like MAPS have been researching Psychedelic Assisted Therapy with a non-classical psychedelic, MDMA (also known as “Ecstasy”). This graphic showing their outcomes for treating PTSD illustrates why I’m so excited about how this sort of seachange could help us improve outcomes:

Right now, only universities and organizations that go through an arduous process of getting approval from the Drug Enforcement Agency can practice with and do research on these substances. That’s because Psilocybin and MDMA, along with most other psychedelics being studied for their therapeutic effects including LSD, 5-MeO-DMT, and Mescaline are considered “Schedule I Substances” by the Drug Enforcement Agency. This means they are federally illegal and considered by the DEA to have, “no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse.”

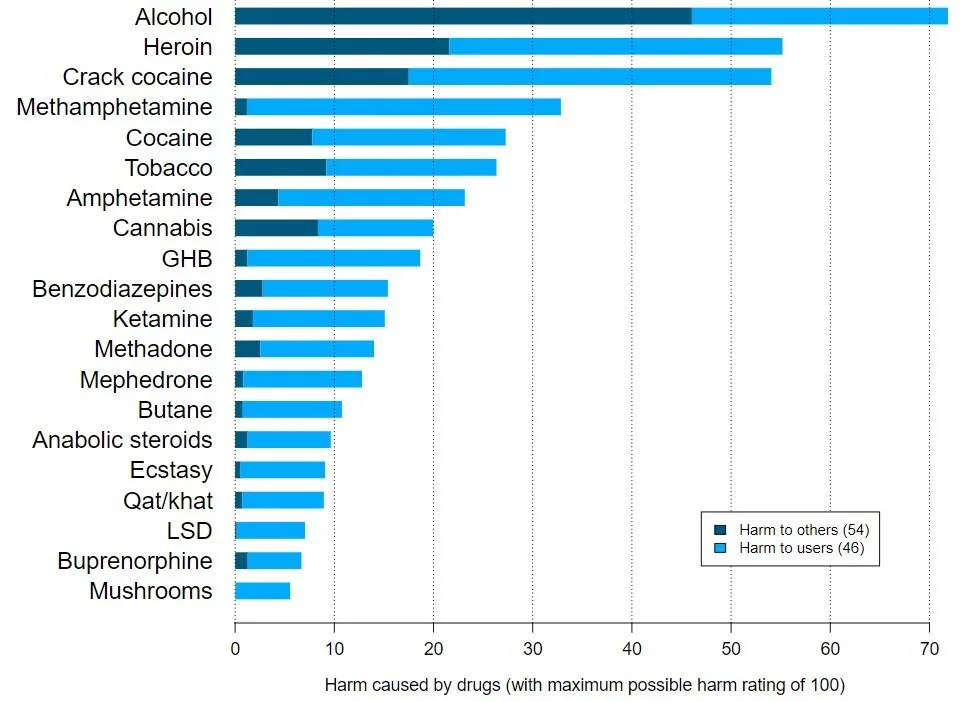

The prohibition on psychedelics is a long story of the culture wars of the 1960s and 70s that continues in an ongoing War on Drugs. Suffice to say, many researchers (and much of the general public) consider the DEA to be flat-out wrong about the medical uses and potential of abuse for psychedelic compounds. They publish papers with graphs like these showing the relative harms of various drugs:

It is notable that LSD, Mushrooms, MDMA are so low on this list, as is ketamine, which is employed in Ketamine Assisted Psychotherapy. This is especially notable compared to the socially acceptable Alcohol, which tops the list. But don’t take this single example as gospel - read other researchers’ takes and look up other discussions on the subject. But I think that review articles like this one, “Assessing the risk-benefit profile of classical psychedelics: a clinical review of second-wave psychedelic research” tell a very tempered story:

“Published studies since 1991 largely support the hypothesis that small numbers of treatments with psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy can offer significant and sustained alleviation to symptoms of multiple psychiatric conditions. No serious adverse events attributed to psychedelic therapy have been reported. Existing studies have several limitations, including small sample sizes, inherent difficulty in blinding, relatively limited follow-up, and highly screened treatment populations.

Substantial data have been gathered in the past 30 years suggesting that psychedelics are a potent treatment for a variety of common psychiatric conditions, though the ideal means of employing these substances to minimize adverse events and maximize therapeutic effects remains controversial.”

We’re starting to have solid knowledge that MDMA, Psilocybin, and other psychedelics help facilitate amazing changes for people who are truly suffering. It’s a shame that these substances remain illegal in the DEA’s list of Schedule I substances. Fortunately, the public is more aware of their potential benefit after the release of bestsellers like Michael Pollan’s How to Change Your Mind, What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence.

Psychedelic Assisted Therapy operates a bit differently than either traditional therapy or psychiatry for mental health issues. It involves a series of therapy sessions called preparation, dosing, and integration sessions. Preparation sessions involve education about the effects of the substance to be used, the setting of expectations including intentions for the outcome of treatment, and advice on how to manage the psychedelic experience all while building trust and a relationship between the therapist and client. Dosing sessions are longer than standard therapy sessions and involve the therapist sitting in the office with the client while they are on the substance and occasionally directing them during this experience. Integration sessions are more like typical therapy sessions that focus on debriefing and conversation to understand the experience and reinforce changes that occurred during and since the dosing session. Basically, -’assisted therapy’ means there are a lot of therapy sessions to talk about and understand the implications of the drug experience rather than just using the substance.

Since we’re largely unable to practice with Schedule I substances (the notable exception to this is getting admitted into one of MAPS limited and selective programs for MDMA training), many therapists interested in developing the skills to practice Psychedelic Assisted Therapy are utilizing other substances with some psychedelic effects. Notably the DEA places Ketamine in Schedule III, recognizing it as a substance with medical use that can be safely prescribed by doctors and employed in Ketamine Assisted Psychotherapy.

Ketamine is a dissociative anesthetic that is on the WHO list of essential medicines and has been approved for the treatment of depression. Its standing use in medicine is as an anesthetic, but there’s a recent body of research showing that infusions of ketamine can be helpful for those with treatment-resistant depression (defined as depression that persists despite attempts with at least two different prescribed drugs). Ketamine Assisted Psychotherapy can create nonordinary states of consciousness somewhat like psychedelics do in Psilocybin Assisted Therapy, creating a unique opening to explore the mind, visual and audio hallucinations, dream-like states, and an enhanced sense of connection.

The non-ordinary state of consciousness occasioned by Ketamine administration has led to many therapists beginning to practice Ketamine Assisted Psychotherapy. While this is an interesting experiment, Ketamine is not nearly the same as the classical psychedelics (LSD, Psilocybin, DMT), which interact with the serotonin system. While the action of Ketamine is not completely understood it doesn’t act on the serotonin system, it seems to primarily work on the glutamate system (see LorienPsych’s page on Ketamine).

Ketamine Assisted Psychotherapy is different from the simple administration of a Ketamine infusion. It’s formatted more like how Psychedelic Assisted Therapy works with multiple therapy sessions for preparation, dosing, and integration.

I’ve asked around for research on Ketamine Assisted Psychotherapy, but it seems the evidence is limited as this, Ketamine Assisted Psychotherapy (KAP): Patient Demographics, Clinical Data and Outcomes in Three Large Practices Administering Ketamine with Psychotherapy, is the best article I was given on the subject. I’m looking forward to well controlled future research comparing the outcomes of Ketamine Assisted Psychotherapy to ketamine infusions alone, therapy alone, and ketamine infusions coupled with therapy that does not focus on integrating the ketamine experience. I believe that Ketamine Assisted Psychotherapy will outperform the other groups but I like to refrain from holding strong beliefs until I have strong evidence.

I’m interested in this area because I think it’s the most promising research programme for significantly improving the ability of therapy to help people get where they want to go. I’m interested in the legal and ethical application of utilizing medicines accompanied by therapy to facilitate positive change for those who are suffering and for the betterment of well people. I’ve begun taking courses on Ketamine Assisted Psychotherapy and Psilocybin Assisted Therapy and I’m eager to meet the people actively working in this area.

New Developments in the Approvals of Psychedelic-Assisted Therapy for Veterans with PTSD

We will likely be seeing further developments into the study of psychedelics for conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder, particularly in the treatment for veterans living with this condition. I am closely following the developments in the Biden administration on this issue, wherein there is an apparent approval by the FDA of MDMA and psilocybin for treating PTSD on the horizon. This would start with “research and pilot programs within the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs.” Read more about the start of this legislative action here.