Blog

Erotic Intelligence: How to Cultivate Healthy Sexuality in Intimate Relationships

Erotic intelligence is a concept created by Esther Perel, a Belgian-born psychotherapist, author of the best-selling book Mating in Captivity: Unlocking Erotic Intelligence. This book discusses the conflict between sex and intimacy that afflicts many modern couples. It’s worth spending time to examine the key concepts of Erotic Intelligence and how to apply them to cultivate healthy sexuality in intimate relationships.

Erotic intelligence is a concept created by Esther Perel, a Belgian-born psychotherapist, author of the best-selling book Mating in Captivity: Unlocking Erotic Intelligence. This book discusses the conflict between sex and intimacy that afflicts many modern couples. It’s worth spending time to examine the key concepts of Erotic Intelligence and how to apply them to cultivate healthy sexuality in intimate relationships.

Erotic Intelligence Summed Up

Esther Perel’s theory of healthy sexuality postulates that the familiarity that comes with intimate relationships is often at odds with our need for tension and exploration of the unknown to cultivate erotic desire. She challenges the romanticized idea held by many couples that the perfect romantic relationship is one in which the other partner can satisfy our every need, acting as our confidant and best friend as well as our passionate lover. The reality of this approach is that it often results in couples becoming bored with the same old thing time and again. To keep eroticism alive in a relationship, it is important to cultivate some distance, surprise, mystery and play. When we step back from our partners and accept them as people separate from us, agents with internal lives entirely free from our own, we create the space for desire to grow.

Quality Over Quantity

While some couples just want more sex, there are many more who want to reconnect with a deeper intimacy that makes them feel alive. The desire for an affair is often not an attempt to hurt one’s partner, but an attempt to rediscover the irresistible desire they once had at the beginning of their relationship. Curiosity and play are keys for healthy sexuality in relationships, and necessary for them to stand the test of time.

Step Back and See Your Partner

Stepping back to view your partner as a separate person involves risk. We abandon the delusion that our partner’s sexuality is solely ours. We may have to confront some discomfort as we recognize that their fantasies transgress the comfortable boundaries of our relationship. But we should call them what they are: fantasies. Exploring the unfamiliarity of this territory can lead to uncomfortable feelings. But leaning on the structure of monogamy, we risk falling into monotony. By acknowledging the agency in choosing the relationship, we own the choices we and our partner are making to turn towards one another.

Resources to Cultivate Healthy Sexuality

Mating in Captivity by Esther Perel

America’s War on Sex by Marty Klein

Magnificent Sex: Lessons from Extraordinary Lovers by Peggy Kleinplatz

Questions to Explore Sexuality

Who is your sexual role model?

How did you figure out how to integrate your sexuality into your identity?

Questions via David Ley, PhD (taken from this talk on YouTube)

FAQs

Why is healthy sexuality important?

Sexuality is an essential part of our humanity, and maintaining sexual connection in relationships is an important aspect of maintaining our relational bond and ensuring our relationships are sources of wellbeing and durable happiness.

What are the characteristics of a sexually healthy person?

Even in healthy intimate relationships, sexual satisfaction is a fluid state. Sexual satisfaction becomes more possible when we have acceptance of our sexual needs and desires as part of our self and act consciously to figure out how to integrate those needs and desires into our life in an intentional manner. In order to let go of shame around sexuality, it can be helpful to recognize that there isn’t one right kind of sexuality. We increase our feeling of sexual liberation and become more sexually healthy when we accept the different aspects of our sexuality and recognize that they aren’t things we get to choose.

How much distance is too much?

Distance is not without problems in relationships. When we step back from the comfort of being with our partners to be more alone, we create insecurity for them and for ourselves. However, this insecurity is often a precondition for maintaining interest, desire and intimacy.

Stepping back doesn’t mean neglecting my partner or separating from the relationship. Distance gives us and our partners space to focus on ourselves and recognize the friends, activities, and aspects of ourselves, like our thoughts and fantasies, which exist outside of the confines of the relationship.

How do I enhance my erotic intelligence?

Erotic intelligence means having the courage to step outside of comfortable routines and pursue the desires and other aspects of sexuality that may extend beyond your relationship. To develop healthy sexuality, you must communicate your needs and preferences to your partner and be open to their needs and preferences as well. As both partners pursue their fantasies, you can achieve sexual satisfaction that isn’t possible by simply maintaining the status quo.

Interview with Reid Nicewonder, the Cordially Curious Street Epistemologist

There’s a contradiction that sometimes occurs when someone comes into therapy. A client will sit down and express certainty about their inadequacy, badness, and helplessness yet they are entering a space expecting to change. They experience the ambivalence between feeling the belief in their badness, inadequacy, and helplessness is true and expecting that it can be shown to be not true.

There’s a contradiction that sometimes occurs when someone comes into therapy. A client will sit down and express certainty about their inadequacy, badness, and helplessness yet they are entering a space expecting to change. They experience the ambivalence between feeling the belief in their badness, inadequacy, and helplessness is true and expecting that it can be shown to be not true. These beliefs deeply affect their wellbeing and their moment-to-moment suffering makes them profoundly aware of it. Their experience of their beliefs matters.

People voluntarily enter a space in therapy expecting to change. But how do beliefs change? Maybe to know that we need to explore a more fundamental question: How do we know what we claim to know?

A few years ago I became very invested in these questions. I discovered that asking the question, “how do you know?” can be a powerful tool. It seemed so fundamental and important I wondered why I had never had a required course in school that focused on this question. Courses do exist on the subject, though. This simple question is central to a branch of philosophy called Epistemology.

Epistemology deals with belief, justification, truth, and knowledge. The nature of what it’s exploring is so basic to human existence, it’s important it not remain confined to ivory towers of academia. Socrates frequented and used the language of the marketplace, bringing his ideas to the people and “corrupting” the Athenian youth.

I’m glad that there are some communities that continue the Socratic tradition. In 2019, I found one of these communities after YouTube recommended videos tagged with Street Epistemology. Someone with a GoPro would ask if he could film the people who approached as they speak about one of their convictions. And in these videos, the person who approached usually seemed to struggle to answer gently posed, deceptively simple questions.

Rather than running into reason, these conversations quickly ran into psychology as people became defensive, flustered, or rationalized something they hadn’t previously thought about. But the Street Epistemologist filming acted like a therapist, staying gentle and calm during these charged conversations.

I sought out more information about the community, talked to some people who did Street Epistemology, which they just called “SE.” They claimed to primarily be interested not in what people believe, but in having conversations that help people reflect on how they come to believe. To have these conversations, they were developing toolkits of managing a relationship built on conversation which focused on growth and change, which meant they were trying to independently develop the skills that therapists go to school to cultivate.

I’m glad to have gotten to know one of these Street Epistemologists who is deeply invested in the community. Reid Nicewonder is the host of the YouTube channel, Cordial Curiosity. Many weekends, you can find him in Runyon Canyon or Echo Park sitting at a table and inviting people to sit down to talk about what they believe and how they think. He was kind enough to take the time to answer my questions on SE.

Below, my questions are in bold with Reid’s responses following.

EA: What is Street Epistemology?

RN: Street Epistemology (SE) is a positive and productive way to help someone reflect on their reasons and motivations for believing something. Its core structure uses the Socratic Method. There are two roles in the conversation – the questioner (SEer) and the person being questioned (interlocutor / IL). Unlike Socrates, whose style and demeanor was like a gadfly, SE focuses heavily on building and maintaining positive rapport. It uses research from applied epistemology, hostage and professional negotiations, cult exiting, and psychology.

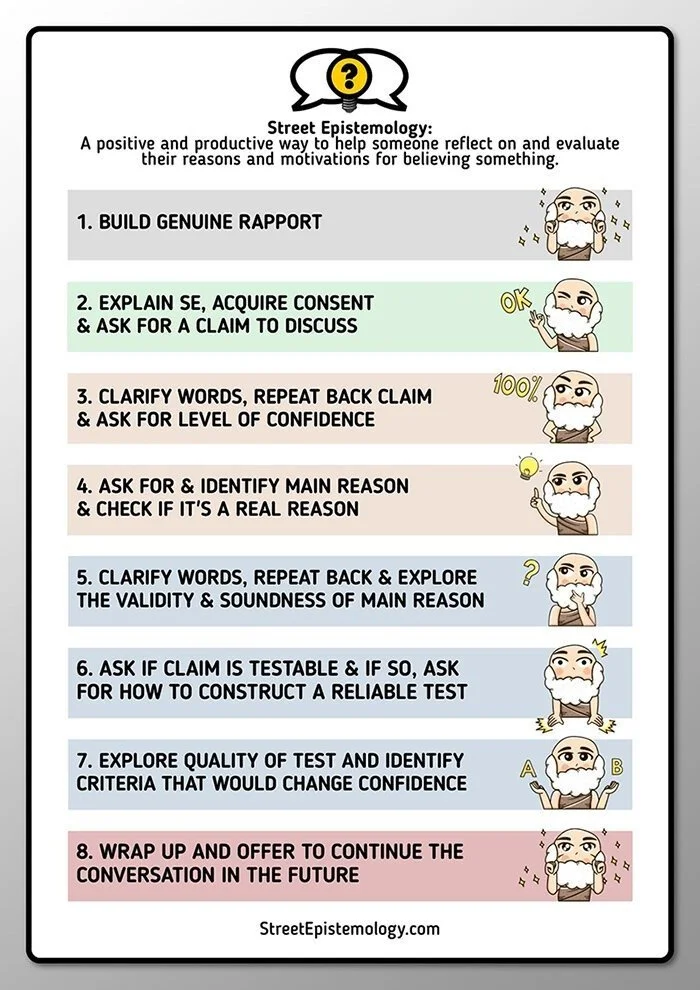

The basic steps of Street Epistemology

A successful SE conversation is when you get to at least one of the blue steps (5 – 7) where you’re exploring the quality of someone’s epistemology while at the same time maintaining the positive rapport you’ve built in step 1 all the way through to the end of your conversation.

How did you get into it?

I originally heard about SE in 2013 after listening to an interview with Peter Boghossian on a podcast. He talked about a different way of having conversations with people about their religious beliefs, one that was potentially much more effective at inspiring reflection. At the time, I wanted to help people think more critically about religion, so I read his book and his advice seemed promising.

It wasn’t until a year later when I came across Anthony Magnabosco on YouTube, who had been uploading examples of SE conversations he was having with the public in San Antonio, that I really got into SE. In contrast to the usual debates I was watching on YouTube, which were hostile and argumentative, Anthony’s conversations seemed calm and effective at helping people reflect on why they believed what they believed. His first videos were a bit rough, but he would post them in the SE Facebook group to get feedback, which he would apply in future conversations.

By 2015, more and more people were uploading their own videos to YouTube. Then a new video chat site called Blab was launched and a bunch of people from the SE community went over there to practice.

Blab allowed anyone to create a public video chat room with up to four people and a chat on the side. So for about a year, myself and many others from the SE community practiced there regularly. When Blab shut down in mid 2016 I was in need of a new place to practice SE.

While I didn’t feel ready to go out and record the way Anthony and many others were doing, reading The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck by Mark Manson inspired me to try to fail-forward. So, one day in the fall, I went to Griffith Park park with a table, two chairs, a mic, a GoPro and started doing public SE interviews.

Reid’s first Street Epistemology setup in Griffith Park

I’m now President of a non-profit dedicated to educating the public about Street Epistemology, supporting the SE community, and obtaining scientific research about its effectiveness.

What are the goals Street Epistemology can help us accomplish? Is SE different from persuasion?

The main goals SE can help us accomplish are giving ourselves an opportunity to understand the reasons that lead someone to confidence in a belief in order to collaboratively reflect on the quality of those reasons. Helping myself and others reason better is my ultimate goal.

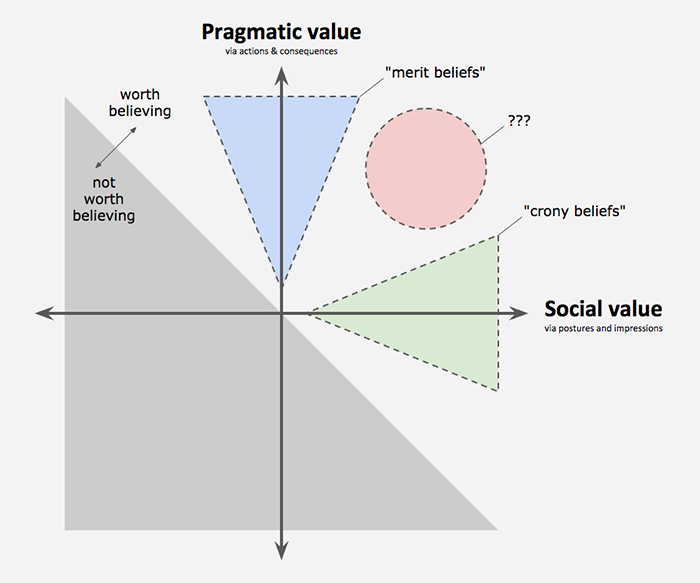

A scale Reid uses for indicating confidence in a particular belief

The usual way people try to persuade is through debate, where someone throws out many facts and arguments hoping the other person will change their mind. While SE can be used to persuade, and wanting to change someone’s confidence may often be a goal, it’s rarely the highest priority goal. With SE, we use discussions about beliefs as a means to explore the quality of someone’s epistemology for the end of helping us all become better critical thinkers. If our general methods of reasoning are good, then the calibration of our confidence level in particular beliefs should take care of themselves.

How do people commonly form and change beliefs?

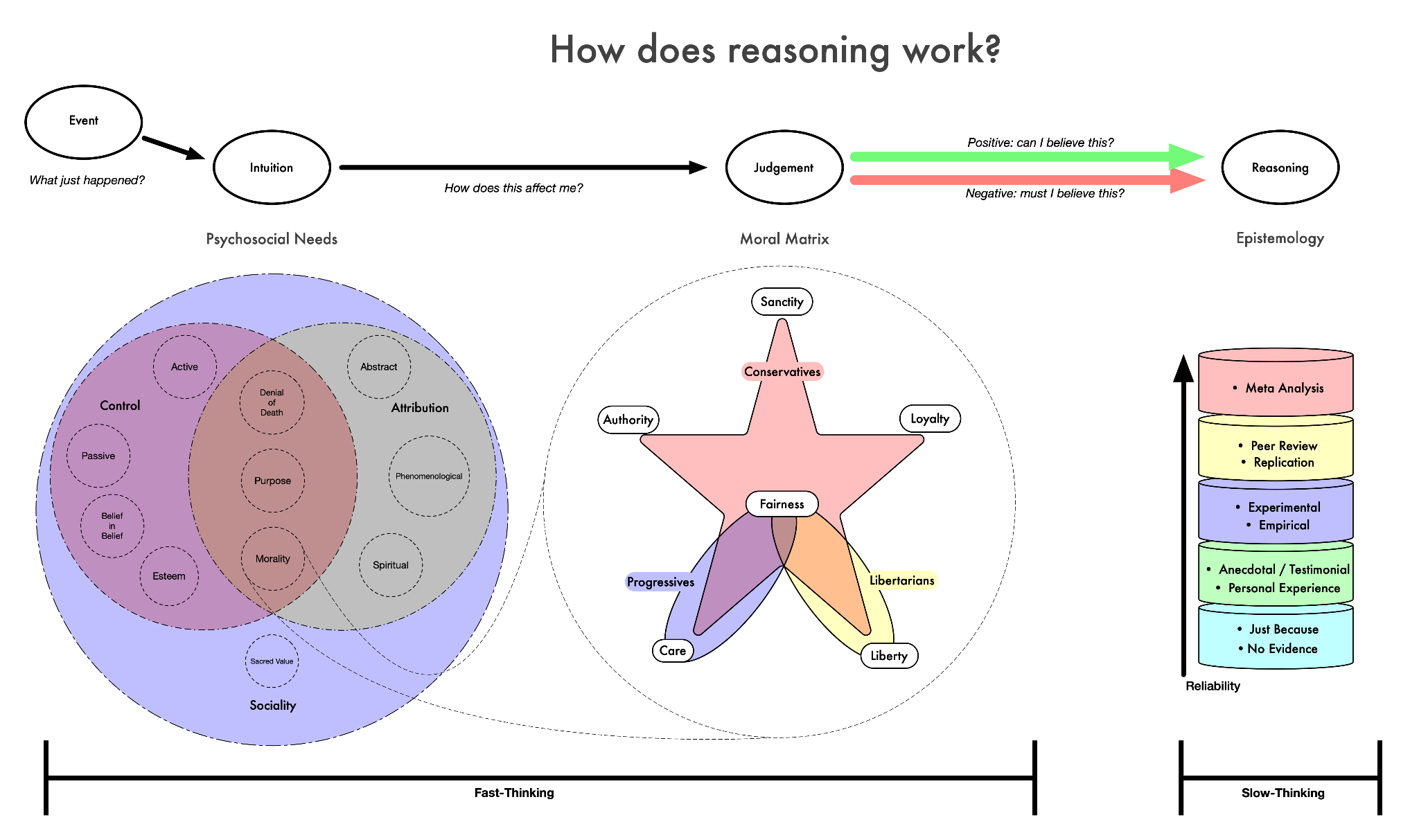

Here is a graphic I’ve been working on to help me make sense of how people’s beliefs work.

Reid’s chart on How Reasoning Works

“Intuition comes first, strategic reasoning second.”

– Jonathan Haidt,

A belief is a feeling of confidence produced by the brain about a concept. When someone encounters a new concept, it passes through a set of unconscious psychological filters, which produces either a negative or positive judgement about the concept. Frequently, reason is only used to support the judgement after the fact, like a press secretary.

“For our beliefs to function as loyalty signals, we can’t simply “follow the facts” and “listen to reason.” Instead, we have to believe things that are beyond reason, things that other, less-loyal people wouldn’t believe.”

– Kevin Simler & Robin Hanson, The Elephant in the Brain

The most common ways we develop and change their beliefs are related to tribalism. Humans are a hyper-social species. We adopt beliefs from people around us who we respect and admire. While beliefs can allow us to navigate reality pragmatically, acting and making choices to further our goals, this is not usually how we form our beliefs. More often, we form beliefs due to social status. This is because beliefs can be a way of blending in, showing off, or cheerleading the sacred values of our tribe to show belonging.

Crony Beliefs by Kevin Simler

How has Street Epistemology helped you understand how people form and change their beliefs?

I started recording interviews at Griffith Park in September of 2016. At that time I was working with the assumption that most people could be relied upon to change their minds in light of discovering their reasons were either fallacious or poorly justified. This did not happen. People left my table with the same level of confidence they sat down with. This made me want to understand what was going on.

I read Everybody Is Wrong about God in early 2016 where I learned about the psychology of religion including the concept of psychosocial needs. Then I read The Righteous Mind in January of 2017 which included the social intuitionist model and moral foundations theory. In January of 2018, I read The Elephant in the Brain which included signalling theory. Understanding the hidden motivations as to why people practice religion, engage in politics, and have conversations in general made my failures conducting SE up to that point make so much more sense. I now recognize the importance of tribalism, morality, and signalling in relation to how and why people come to their beliefs.

Once I started practicing SE with all of these psychological models in mind, my conversations became much more productive. For example, if I hit a roadblock at the level of reason and evidence, I would go deeper and start to ask probing questions to try and discover how the belief provided a way to meet one of my IL’s psychosocial needs. Once we identified a psychosocial need, I’d help them brainstorm alternative ways to meet it. This allowed my IL to feel more safe and open to talk about the belief and their epistemology and much more genuine reflection occurred.

What is the difference between good and bad epistemology?

“A wise man proportions his belief to the evidence.”

– David Hume

Good epistemology helps us have a reasonable level of confidence about any claim. If our confidence is too high or too low, we’ve used a bad epistemology.

There is a particular set of rules that are reliable at producing reasonable confidence levels with the least amount of conflict. “We have to draw conclusions in life... but we must all take seriously the idea that any and all of us might, at any time, be wrong.” That is to say, we are all fallible. “If you are not inclined to doubt, you never even reach skepticism—it is simply not an issue; you simply believe without asking questions.” Deciding to have this attitude leads to two rules we should follow:

“No one gets the final say: you may claim that a statement is established as knowledge only if it can be debunked, in principle, and only insofar as it withstands attempts to debunk it.”

“No one has personal authority: you may claim that a statement has been established as knowledge only insofar as the method used to check it gives the same result regardless of the identity of the checker, and regardless of the source of the statement.”

This is what Jonathan Rauch in Kindly Inquisitors calls the game of liberal science. If an epistemology violates these rules, it’s a bad epistemology.

In Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, we often discuss adaptive versus maladaptive beliefs where this is referring to whether beliefs are helping people achieve their goals and live a life worth living. Do you think that this is a valid way to talk about beliefs?

I do. Fitness is not the same thing as truth but they’re highly correlated. The more accurate a map we have of the small pocket of reality we’re in, the better we can navigate it. But sometimes truth and fitness conflict. For example, if I’m around a gun that I know is unloaded, the value of the belief, “all guns are always loaded,” influences my behavior around guns in general, even though I’m virtually certain this particular gun is harmless.

There’s a distinction between epistemic rationality and instrumental rationality. Epistemic rationality is about having an accurate map whereas instrumental rationality is about knowing how best to navigate the map in accordance with your goals and values. If my confidence is more than the actual probability that the gun is loaded, then that belief would be instrumentally rational but epistemically irrational.

How are our beliefs related to our wellbeing?

Our beliefs influence our wellbeing in many ways. They influence how we perceive the world and our actions, which then have consequences. Some actions are more reliable than others for increasing our wellbeing. Our beliefs dictate which actions we take to try and achieve our goals and they dictate which goals seem worth pursuing.

‘What produces human wellbeing?’ is an empirical question. That is, to answer that question we must experiment and observe what happens. It would be in our best interest to have our beliefs align with an accurate model of reality, including an accurate model of what reliably produces wellbeing. Reality always bats last, and bumping into reality can produce immense suffering, not only for ourselves but for others.

What are the helpful lessons an average person can take away from Street Epistemology?

Questioning is more effective than telling in order to help people reflect. Conversations about contentious and deeply-held beliefs don’t have to be argumentative. People are not their beliefs. It’s possible to persuade while maintaining a good relationship, or as we say, positive rapport.

What are the ways people can become involved with Street Epistemology?

The SE website is a great place to start. I highly recommend the SE Discord for a place to practice or get your questions about SE answered. The SE subreddit is nice for keeping up with new content that’s being created.

If you really want to get involved, SE has its own non-profit, Street Epistemology International. There are always big projects that are in need of volunteers and funding. We are currently in the development of a huge training course for SE. SEI can also help people fund their own SE projects.

Thanks so much for taking the time to answer these questions. If people want to sit down to chat with you, where can they find you?

In person, they can find me at Runyon Canyon in Los Angeles on most Sunday afternoons. Join the SE Los Angeles Meetup for more specific info. Or they can chat with me privately on Zoom by scheduling a time here.

Thanks so much, Erik, for the interview!

Anxiety Part Two: Anxious Like Me

To the best of my understanding, theories of emotion are attempts to answer the question, “WHAT IS THIS FEELING, WHY DO I HAVE IT, AND WHAT’S WITH THIS SALTY DISCHARGE COMING FROM MY EYES?” Thankfully, we’ve mostly outgrown humour theory, so relatively few people still say you’re depressed due to an excess of black bile. But then again, within the last month, I heard people attribute feeling states to another ancient theory of medicine...

“Oh your “brain” is acting “illogically”? It’s meat with electricity inside, what the f*ck did you expect”

~Twitter user @KylePlantEmoji

IV

To the best of my understanding, theories of emotion are attempts to answer the question, “WHAT IS THIS FEELING, WHY DO I HAVE IT, AND WHAT’S WITH THIS SALTY DISCHARGE COMING FROM MY EYES?” Thankfully, we’ve mostly outgrown humour theory, so relatively few people still say you’re depressed due to an excess of black bile. But then again, within the last month, I heard people attribute feeling states to another ancient theory of medicine. So, while the numbers have become fewer, they’re still nonzero.

One way to explain emotions is to look at the systems that are involved when emotions arise. A number of theories have arisen that divide along the lines of whether emotions should be viewed as governed primarily by physiological (James-Lange Theory), neurological (Canon-Bard Theory), or cognitive (Appraisal Theory of emotion) systems. These different theories emphasize, respectively, that emotion is primarily a phenomenon of the body, the brain, or the mind. There’s clearly a role each plays, but there is division between the theories with regards to what we ought to consider the primary phenomenon which we call “emotion.”

In his lectures on human behavioral biology, American neuroscientist Robert Sapolsky gives us a perspective on the cascade of processes that underlie emotion:

“It’s not the case that your brain decides it’s feeling an emotion based on sensory information coming in, memory or whatever. It’s not that the brain decides it’s feeling an emotion and tells the body let’s speed up the heart, let’s breathe faster, let’s sweat, or whatever it is. That’s not how emotion works. Here’s how emotion works: stimulus comes into your brain and before you consciously process it, your body is already responding - your heart rate, your blood pressure, your pupillary contractions, whatever.

How do you figure out what emotion you’re feeling? You get information back from the periphery telling you what’s going on down there. In other words, how do you figure out you’re excited? Whoa! If I’m suddenly breathing real fast and my heart’s beating fast, it must be because I feel excited now.

Ridiculous. Totally absurd way in which you process stuff. Completely inefficient. And, over the years, after decades of being wildly discredited, more and more evidence that is some of how emotion is based: your brain being influenced by your bodily state to decide which emotions it’s feeling.” (from Sapoksly’s lecture on the Limbic System)

Sapolsky is great for his ability to engage with the ridiculousness of the systems evolution provided us with. You can tell he sees the humor in the humanity of it all. He expresses incredulity at the body of evidence which suggests that we experience emotions in a roundabout way: brain systems well outside of our consciousness respond to stimuli, changing the physiological state of the body... then brain systems partially within our consciousness feel what the body is doing and get around to naming that feeling. In his whimsical style, Sapolsky is throwing his hat in with something like physiological-neurological theories of emotion.

V

To truly understand emotion, we need to spend time understanding each of the different aspects outlined in the previous section. Emotion is a physiological, neurological, and a cognitive phenomenon. So while Sapolsky gives credence to something like a physiological-neurological theory of emotion, in this section I’m going to look at why we might give credence to cognitive theories of emotion.

Sapolsky said we eventually get around to naming the feeling. But what is that process? Naming the feeling is the process that American psychologist Richard Lazarus emphasizes. Lazarus was one of the progenitors for cognitive theories of emotion and, more specifically, cognitive appraisal theory of emotion.

His work took off in the 60s and helped bring American psychology out of the limited examination of behavior and into the study of cognition. Lazarus’ cognitive appraisal theory of emotion emphasizes the role of our mind’s capacity to place physiological sensations into context to assess what’s going on.

In Emotion and Adaptation, Lazarus connects emotions to reflexes and drives. Reflexes, drives, and emotions are responses that help us meet our needs in our environment. But they differ in the rigidity of their response. Reflexes, like startling or blinking, are largely involuntary fixed patterns of action — the response is basically the same each time. Drives like hunger and thirst motivate predictable classes of behavior, but the particulars of the response can vary. Emotions, like anger or anxiety, allow for much greater flexibility in response.

Emotions arise subsequent to stimuli. The stimulus can be internal or external, real or imagined. But the stimuli that give rise to emotions are related to each other in that they signal something significant for well-being may be at stake. The brain quickly interprets the stimulus and assesses whether it is salient for survival. If the stimulus is assessed to be salient for survival, this leads to a complex reaction of the body and mind which fuses thought, motivation, impulse, and physiological changes. Our reactions are processes that occur in the brain and body, which can be schematic or conceptual. Schematic processing is passive and automatic. Conceptual processing is conscious and deliberate.

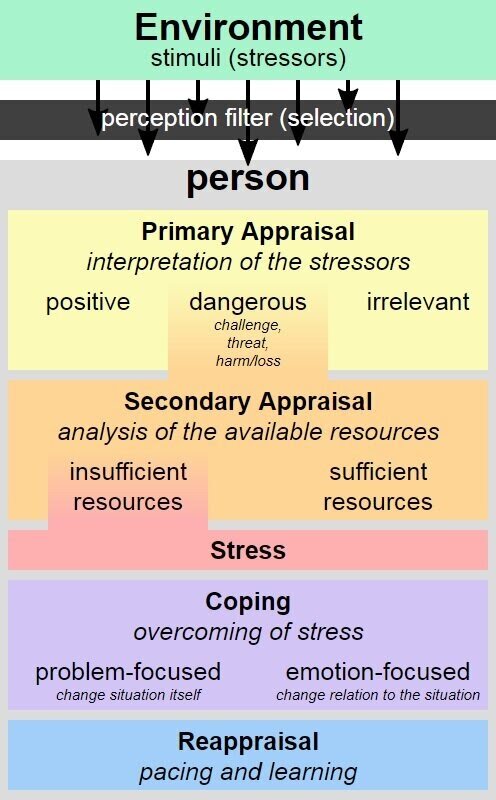

I was interested in what Lazarus’ cognitive appraisal theory of emotion has to say about anxiety, and thankfully Wikipedia has a colorful model of Richard Lazarus’ Transactional Model of Stress and Coping, which may help illustrate how we worry:

Lazarus’ cognitive appraisal theory of emotion regards each emotion as having a “core relational theme” of the individual relating to the situation. Anxiety’s core relational theme is interpreting ambiguous dangers or uncertain threats in the situation.

The graph above illustrates the process that leads to the emotion arising. Stimuli is perceived. That sense data is modeled in the mind in the primary appraisal process where we generate knowledge/belief about the situation and assess whether the situation is positive, irrelevant, or dangerous. We then assess whether we have the right resources to maintain personal well-being in the situation. If it is determined that resources are not present, it contributes to the anxious theme of uncertainty. Coincident with these negative assessments, the emotion of anxiety is produced. We feel the stressful emotion and begin to seek out ways to overcome anxiety by either managing the problem or the internal emotional process.

In Lazarus’ cognitive appraisal theory of emotion, this subjective interpretation of stimuli is affected by biology, personality, and culture. Because emotions arise out of our interpretation or evaluation of a stimulus, emotion has moved from a concrete event to an abstract meaning. Since we’re responding to an evolving interpretation called meaning, our emotional response is dynamic and tracks the changes in the environment for their significance to our well-being but also tracks the changes in our thoughts and beliefs which assess the situation.

Assessments are flexible and subjective. I interpret things like sweating and elevated heart rate differently depending on the situation. If I’m watching sports, it’s excitement; If I’m exercising, it’s exertion; and if I’m in a meeting, it’s anxiety. This interpretation is not within our momentary volitional control. But in his cognitive appraisal theory of emotion, Lazarus has identified that we can intervene in the process of emotional response through something we might generally call “coping.” We learn to cope with different stimuli, and this coping mediates our emotional response. Just as we can change our habits and beliefs over time, we can adjust our emotional responses.

We all experience growth in our ability to cope internally. Growing out of childhood, we stop interpreting small hungers or pains as crises and rarely respond with the same anguished tearfulness. Learning to swim, we stop experiencing fear and panic at the sensation of water on our faces. Albeit, we may still panic at the feeling of water on our face if it’s thrown during a dinner party.

Lazarus’ cognitive appraisal theory of emotion, falls in between seeing emotions as innate, fixed products of our biological heritage, and sociocultural, following scripts that vary widely across cultures. That is, it does not ignore the physiological and neurological aspects even while giving primacy to the cognitive aspect. This cognitive theory of emotion connects emotions to the biological processes of drives and reflexes, highlighting that emotions come with predictable autonomic, hormonal, and facial expressions. But it also allows room for personality factors that arise in diverse cultural settings.

While not all thought is volitional, our ability to respond to our thoughts is well within our voluntary control. Part of what is compelling about cognitive theories of emotion is how they give us a place to intervene in stress: in the way we interpret our relation to the situation.

While Lazarus’ theory is all well and good and seems to check out with my own internal experience… so does Sapolsky’s description of emotions. I can imagine each of these theories of emotion being true despite them contradicting each other regarding what phenomenon is primary in emotion.

Maybe there’s something I’m missing. I’m tempted to settle this with an appeal to data from experiments — it’s certainly possible that recent experiments have been resolving the disputes between these different theories of emotion. However, it’s really hard to have objective experiments determine something about such a subjective phenomenon.

Incredible experiments based on objective data are what have allowed us to make advances in neuroscience… just look at the debate over free will! Those who discuss this other subjective phenomenon commonly make reference to the study where the awareness of deciding on a choice occurred at a distinctly later time than the unconscious neural activity which initiated acting on the choice. Sapolsky makes reference to similar research in his discussion on feelings above… but even his statement doesn’t completely rule out that cognition could be primary in emotion.

What’s funny about this topic is the extreme epistemic uncertainty we have about it. These theories contradict each other regarding what feelings primarily are. And those disagreements seem to be in part occurring because we don’t really understand what consciousness is — which is ridiculous because it’s literally all that we can possibly be aware of. Am I barking up the tree of the hard problem of consciousness? It sure seems we know a lot more about the thing-in-itself rather than the phenomenal experience of the thing.

I’M A THERAPIST WHO WANTS ANSWERS, DAMMIT! I REQUIRE MORE OBJECTIVITY ABOUT SUBJECTIVITY!

I’m the kind of person to struggle against epistemic uncertainty so I’m not giving up on the topic of what emotions are or the project of digging into everything I can to understand anxiety. In the next post, I’ll wade back into this swamp and brave the miasma as I try to discuss the neurological underpinnings of emotion, honing in on the processes within the brain which produce the experiences we call emotions. I’ll attempt to do justice to the findings of neuroscientists like Damasio and Friston. Make sure to follow my blog to read the next installment.

Art and Science III: SlateStarCodex on Gottman

Scott Alexander, my favorite writer on the interweb, has been reviewing therapy books and got around to a particular specialty of mine, couples therapy. He reviews John Gottman’s landmark book, Seven Principles for Making Marriage Work...

Scott Alexander, my favorite writer on the interweb, has been reviewing therapy books and got around to a particular specialty of mine, couples therapy. He reviews John Gottman’s landmark book, Seven Principles for Making Marriage Work. And, in the process of the review, he skewers Gottman. If you’re a couples therapist, you have to read the post. It’s a sober but hilarious takedown of the haughty claims so commonly made in our field.

As a couples therapist who is a religious SlateStarCodex reader, I felt compelled to write a response in the comments (which I’ve reworked into this blog post). I read Gottman’s books before I was into SlateStarCodex and rationality, and before I was into the research on what makes psychotherapy work. Scott’s post expresses many of the same sentiments I have had about the field recently.

John Gottman claims he can observe a couple interact for five minutes and with 94% accuracy predict whether they will divorce within five years. But Gottman’s prediction is actually a postdiction… and it’s a claim that’s quite similar to claims about the success of one treatment style over another – fast and loose with the data and uncritical in regards to methods. Even the study in his FAQ, which he claims is the one that’s truly predictive, admits it’s a post hoc analysis in the abstract (there appear to be two different studies he could be referring to but it’s true for both of them: one, two). It’s another frustrating instance of scientists wildly overstating their claims in public statements while being forced to make more reserved statements in the text of the actual paper that will be scrutinized by their peers.

The Heart and Soul of Change: Developing What Works in Therapy has a chapter on what works in Marriage and Family Therapy. It states, “A critical review of the differential efficacy data demonstrated few exceptions to the dodo verdict when allegiance is considered, comparisons are fair, and bona fide treatments are contrasted, eroding claims of differential efficacy and giving credence to the claim that all have won prizes.” (p.365) They also note that in research on couples therapy, Allegiance effects are a significant issue, as they are in all psychology studies comparing treatments. “Allegiance is the researcher’s belief in and commitment to a particular approach… [it] can exert a large influence on outcome in comparative studies.”

So Gottman’s particular principles are not listed as a definitive element of effective marriage therapy. It seems the Building Strong Families Program would also suggest that the elements described by Gottman don’t, as a general rule, necessarily generate a positive impact on couples.

This shouldn’t be a surprise. It is what we should expect.

Spending a lot of time focusing on The Great Psychotherapy Debate, I’m tempted to say that effective couples therapy follows the same principles outlined in that book. That is, therapy works not when we have specific ingredients for certain disorders (eg. exposure for PTSD, response prevention for OCD, challenging negative cognitions for Depression, reducing negative cycles for Marital Conflict) but because of an alliance in a relationship with a healing figure who agrees with you on your goals, provides an adaptive explanation for the problem that is accepted by the client(s), and clearly delineates where the client can put in effort towards making a positive change. See Wampold’s article on effective therapists for the briefest statement on what effective therapy should be.

I think this has left me with a better model (better at making predictions about outcomes) than I had in the past. I would bet on the claim that specific ingredients (eg. Tackling the Four Horsemen) or adherence to a treatment protocol (eg. Oppa Gottman Style) are not predictive of outcomes in couples therapy. So, in my view, it won’t be a particular model that we can recommend to clients. I would bet on the claim that the couples’ rating of the alliance (eg. “I feel heard, understood and respected by the therapist”), goal congruence (eg. “we talked about what is important to me”), and approach (eg. “the therapist’s explanation of the problem and way of working on it make sense to me”) will be a significantly better predictor of outcome. So, in my view, it means there will be particular therapists that you can recommend to clients.

Does this mean that anything works in individual/couples therapy? No, we do need a clearly defined model and method to explain and work on the problem. But other factors are much, much more predictive of outcome than what model/method we choose. Does the ambiguity there mean we are taking in gullible marks? Does it mean we’re just giving placebos? I don’t think that’s the right way of looking at it (and if it’s true it may “prove too much” about medicine in general). I think a better way of looking at it is “we are in the business of encouraging the process of healing and change. How can we improve our ability to foster that in our patients?”

To work well with couples you need to be confident in your ability to assess, interrupt and discuss the dynamics of the dyad in real time. I don’t think people who have just done ‘a little couples counseling on the side’ are the right people to refer couples to. In couples work, we have to navigate the tricky business of remaining neutral in conflicts. To do so requires viewing problems in the couple as invariably A. part of a dynamic of the system, where B. both members of the couple play a part in reinforcing the dynamic, and C. “bad” behavior is the result of historical trauma and/or presently hidden fears.

To improve my outcomes, I try to elicit, accept and enact feedback from my clients about what they would find helpful from me in the room. I base this on Scott Miller’s work on feedback in psychotherapy. I’m excited to attend my first Feedback Informed Treatment workshop next month. Going through Scott Miller’s blog, I noticed a reference to a recent paper by Norcross showing that patients prefer more directiveness than therapists would prefer to give. If we want our outcomes to get better, we need to take client’s feedback on their preferences into account.

I’m a more directive therapist to begin with but for some clients I sit back a lot and with others I lean forward. With couples, I find that in general it is necessary to take up a lot of space in the room. That means interrupting to point out something that’s being enacted. But it can also mean catching a couple in the middle of a conflict where they are both physiologically aroused. To effectively do this means noticing the arousal, interrupting and distracting by discussing a tangentially related topic for a few moments. Then point out the tactic, discuss physiological arousal and return to the conflict topic with a gentle startup (lol, Gottman). It’s definitely “a firmer hand” in that it’s directive, interrupting, and much more talking on the part of the therapist.

In the wake of Scott’s post, I’ve been talking about couples work with friends. They asked me what styles I employ and I was hesitant to reply (given what I said about comparing modalities in these posts) but when push came to shove, I identified Structural Family Therapy, Satir Family Systems, Gottman, and Emotionally Focused Therapy. I find it helpful to have many tools that I can deploy depending on what I find my clients in the room need at that moment.

Being a therapist places us loosely within what we could call the “helping” or “healing” professions. That vague box is a tricky place to be. I’ve come to realize it requires a continual effort to learn how to help and heal more effectively. Sorting through claims about what works and what doesn’t is part of that ongoing project for me.

Art and Science II: The Great Psychotherapy Debate

For the better part of a year, I have been reading Bruce Wampold’s book, The Great Psychotherapy Debate. It’s a white paper examining the evidence for two competing models of interpreting the research on outcomes in psychotherapy. The competing models for interpreting the research are The Medical Model and The Contextual Model...

I

For the better part of a year I have been reading Bruce Wampold’s book, The Great Psychotherapy Debate. It’s a white paper examining the evidence for two competing models of interpreting the research on outcomes in psychotherapy. The competing models for interpreting the research are The Medical Model and The Contextual Model.

The Medical Model posits that mental illnesses are like any other disease. In medicine, to treat a disease, we develop treatments with specific ingredients that remedy the particular deficits that cause the symptoms.

The Contextual Model posits that treatments with a cogent rationale accepted by the client, administered by a clinician who the client has a therapeutic relationship with, and involving therapeutic actions that the client expects will help, will lead to a health-promoting change.

The book frames this examination by using the ideas of one of my favorite philosophers of science, Imre Lakatos. It outlines how these two models act as competing research programmes. To get an idea of what that means, you can listen to Lakatos describe his theory on the philosophy of science in this lecture he gave to the BBC:

Philosophers of science argue about what should be considered science vs what should be considered pseudoscience. This is called “the demarcation problem.” Karl Popper believed the most important part of the demarcation problem was that a theory must be falsifiable to be called science (for a great critique of Popper’s position see fakenous’ article). Thomas Kuhn described science in a more sociological way, where “normal science” is disrupted by anomalies which led to the paradigm shift of a scientific revolution.

Lakatos’ view on science is to call something a scientific research programme if it has theories that explain observations and has had novel predictions that could have been falsified. Various research programmes exist at the same time, each with a hard core of theories that cannot be abandoned without abandoning the programme altogether. This hard core is protected by more modest and specific auxiliary hypotheses which help interpret data which seems anomalous. These auxiliary hypotheses can be generated or abandoned as needed. A research programme is progressive if it’s changes to its auxiliary hypotheses help it explain and predict new data and degenerative if it has been doing a poor job at explaining/predicting new data.

This view was an attempt to blend the normative views of Popper with the revolutionary structure described by Kuhn. But Lakatos thought Kuhn’s version of “normal science” and “revolution” were oversimplified, instead describing research programmes gaining adherents if they were more progressive rather than spurring a radical paradigm shift. His demarcation involves calling ‘science’ that which has a history of novel predictions (a programme) and which is progressive (updating in a successful way) in its ongoing explanations of and predictions for incoming data.

II

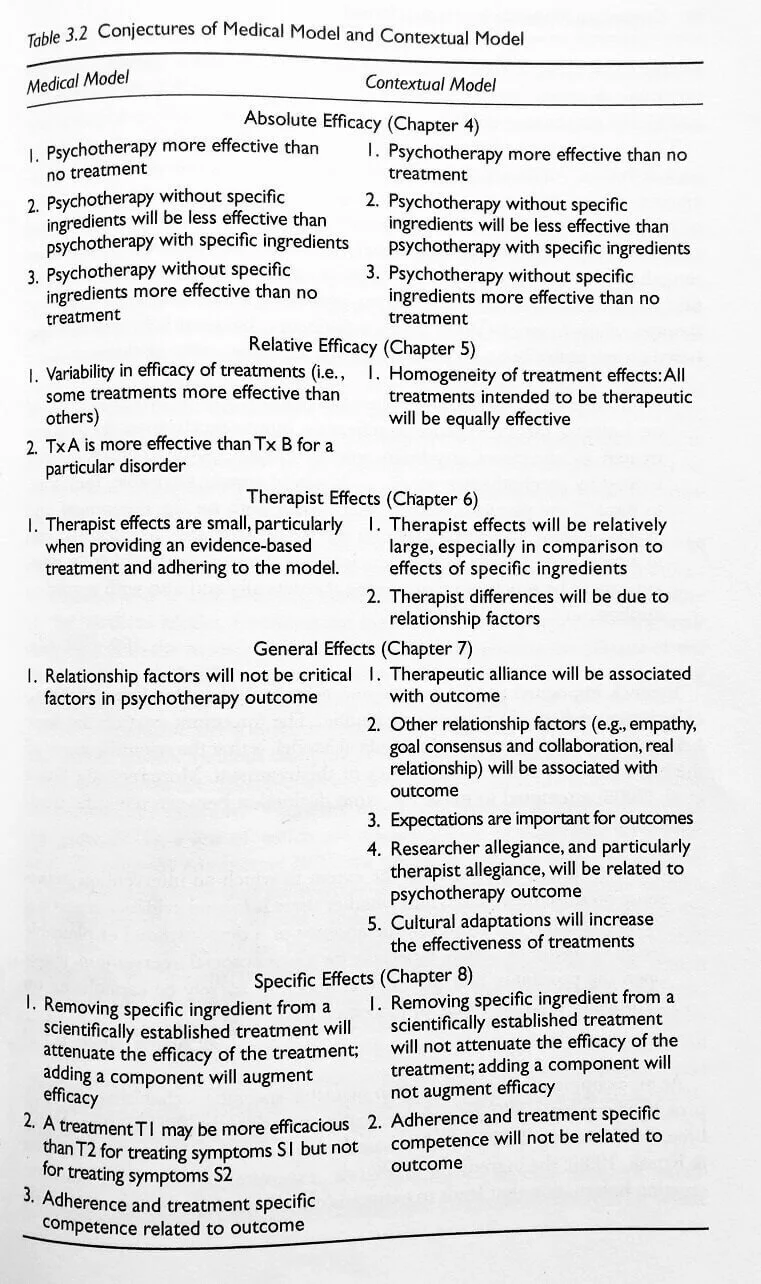

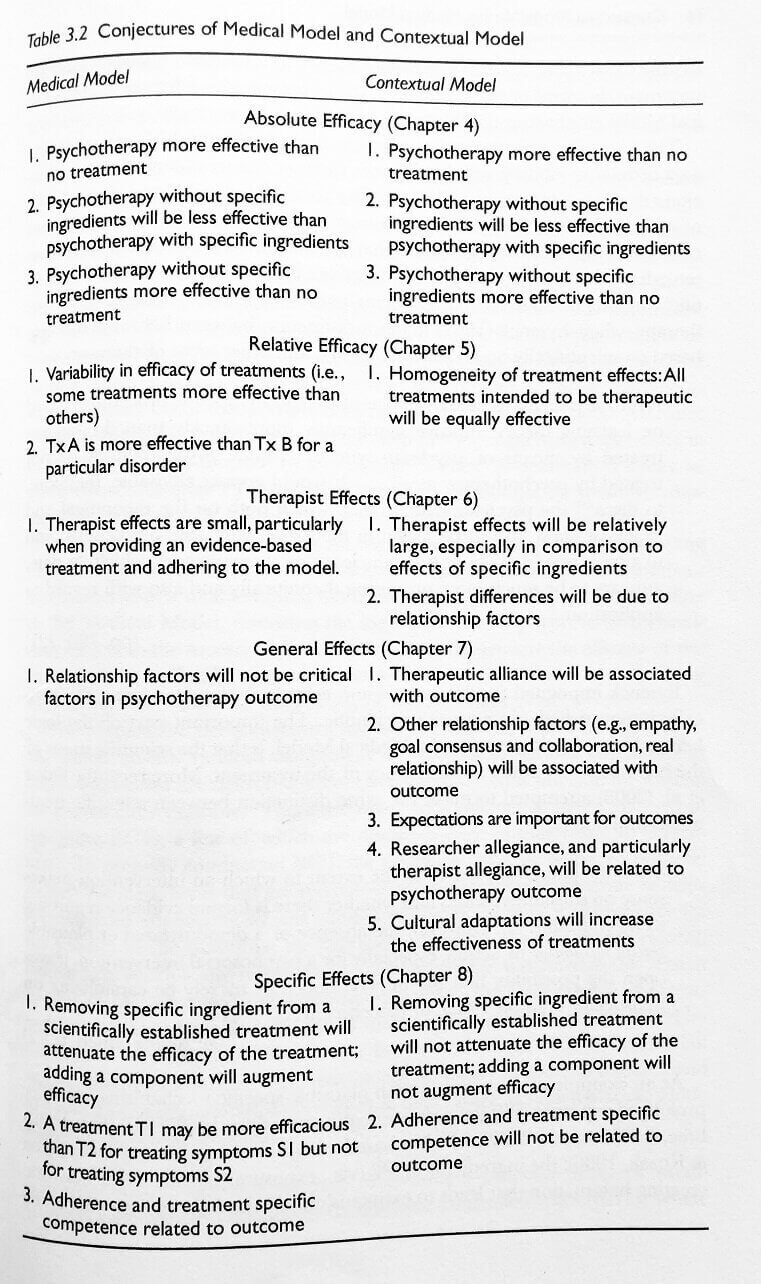

The Medical Model and The Contextual Model are two different research programmes which make very close predictions. But there are specific ways the hypotheses can be teased apart and tested and I think The Contextual Model is the more progressive programme. Here is the table from The Great Psychotherapy Debate where Wampold lays out the conjectures of each programme:

These are a list of conjectures that each research programme makes in order to predict and interpret data on the practice of psychotherapy and the results of psychotherapy outcomes research. Notice the predictions for "absolute efficacy" are identical in both models. The models diverge from there in examinations of "relative efficacy," "therapist effects," "general effects," and "specific effects."

Last year I spoke to one of my professors who was the director of the MFT program at CSULB which I attended. She's a trauma researcher and allied to The Medical Model. In our conversation about what works in treatment, I was arguing for The Contextual Model, saying I believed "relationship factors" are more important than "specific ingredients." (Contextual Model 6.1-6.2)

She argued that treatment for post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) proved that The Medical Model was correct, saying , "I've had many patients come into treatment with me who had a great relationship with their previous therapist but their PTSD symptoms had not gone away. But upon doing prolonged exposure treatment in my clinic, their symptoms went away." Her claim was that a specific ingredient (prolonged exposure) is necessary for the effective treatment of PTSD. (Medical Model 8.1)

Both models predict that some sort of specific ingredient is necessary (Medical Model 4.2, Contextual Model 4.2). So what is the difference between what they’re claiming?

The Medical Model claims that specific ingredients target specific symptoms and therefore, adherence to a specific manual for treatment will be associated with outcome (Medical Model 8.1, 8.3). The Contextual Model claims you need a number of things to get a positive outcome: 1. A relationship 2. An adaptive rationale for the problem which is accepted by patient and therapist which provides hope and expectancy for change 3. A ritual which the patient and therapist perform into which effort is exerted. It’s claim is therefore that you need a clear explanation and ritual but the removal of a particular specific ingredient will not be associated with outcome. (Contextual Model 8.1-8.2)

That is to say - Dr Ghafoori was right to say that the strong relationship is not enough. Both models predict that a relationship without a clearly defined rationale for treatment and a ritual to be performed for treatment will be insufficient.

But her interpretation of The Medical Model would predict that any treatment lacking in exposure would not alleviate PTSD symptoms. The hypothesis she implied is directly out of The Medical Model: competence with and adherence to a treatment manual involving exposure will predict outcomes (Medical Model 8.3). Alternatively, The Contextual Model’s hypothesis is that a ritual that is accepted by the client and therapist must be performed (Contextual Model 4.2) but it will be therapeutic alliance, relationship factors, expectations, allegiance to the treatment, and culturally appropriate adaptations which predict outcomes (Contextual Model 7.1, 7.2, 7.3, 7.4, 7.5).

III

How can we test this? Well, first we can look at what The Medical Model says about PTSD. The medical model predicts there are specific ingredients that are required for successful symptom reduction: 1. targeting triggering stimulus through exposure to extinguish the affective response 2. targeting negative thoughts and beliefs that arise after the traumatic event through cognitive restructuring.

A treatment for PTSD was developed with neither of these specific ingredients. This treatment was called Present Centered Therapy and was developed initially as a pseudo-placebo control that had a cogent rationale (adaptive explanation) and therapeutic actions (a ritual). A 2014 meta analysis determined this treatments effectiveness was similar to previously established Evidence Based Treatments for PTSD such as Prolonged Exposure.

The effectiveness of a treatment without the specific ingredients hypothesized as necessary by The Medical Model directly contradicts it's prediction (Medical Model 8.2, 8.3)

So now we have to ask if the predictions of The Contextual Model (Contextual Model 7.1, 7.2, 7.3, 7.4, 7.5) do a better job.

Is therapeutic alliance associated with outcome? (Contextual Model 7.1)

Yes: “In sum, the overall relation between alliance and outcome in individual psychotherapy is robust, not effected by the file drawer problem, and accounts for approximately 7.5% of the variance in treatment outcomes.” (Horvath et al. 2011)

Are relationship factors associated with outcome? (Contextual Model 7.2)

Yes: The APA’s task force on Evidence-Based Relationships and Responsiveness considers collaborative relationships including goal consensus, empathy, feedback, and a positive regard as a demonstrably effective in enhancing psychotherapy outcomes. (APA 2019)

Are expectations important for outcomes? (Contextual Model 7.3)

Everyone seems to cite neuroscientist Fabrizio Benedetti on this. The most relevant quote I could find from him seems to suggest that yes, they are important: “Hidden administration of therapies has provided compelling evidence that expectation is a key element in therapeutic outcome (Benedetti et al., 2011c, Colloca et al., 2004). If the patient is unaware that a treatment is being performed and has no expectations about any clinical improvement, the therapy is not as efficacious. This has profound implications in terms of medical practice because the information delivered by health professionals can impact therapeutic outcome.” (Benedetti 2013)

Is researcher allegiance related to psychotherapy outcomes? (Contextual Model 7.4)

Yes: “Researcher allegiance (RA)-outcome association was robust across several moderating variables including characteristics of treatment, population, and the type of RA assessment. Allegiance towards the RA bias hypothesis moderated the RA-outcome association. The findings of this meta-meta-analysis suggest that the RA-outcome association is substantial and robust.” (Munder et al. 2013)

Are culturally adapted treatments more effective? (Contextual Model 7.5)

Yes: “The results provide evidence that culturally adapted psychotherapy produces superior outcomes for ethnic and racial minority clients over conventional psychotherapy by d = 0.32. The outcome differences favoring culturally adapted treatment were moderated solely by cultural adaptations of illness myth” (Benish et al. 2011)

IV

The Medical Model and The Contextual Model are competing research programmes. Presently, The Medical Model is the dominant research programme or, in Kuhn’s terms, the “normal science” of our field. The researchers within The Medical Model have been developing Evidence Based Treatments (EBTs) that contain specific ingredients to target specific symptoms for decades. But our outcomes are stagnant. Despite the efforts to develop EBTs, psychotherapy hasn’t improved in its ability to help people since we began measuring its effectiveness in helping people in the 70s. Since the project to develop specific treatments to remediate the symptoms of psychological disorders hasn’t borne out the promise of better outcomes in treatment, The Medical Model is a degenerative research programme.

The Contextual Model makes a number of predictions about what accounts for outcomes in psychotherapy. There’s an enormous amount of variation in the quality of scientific evidence but I believe the meta analyses and expert reviews I’ve linked here are high quality. The predictions of the contextual model have been borne out in the data. Taking the Lakatosian view, I believe the accuracy in the explanations and predictions of The Contextual Model make it the more progressive research programme. The Contextual Model is still a minority voice but I predict that over the next 10 years, The Contextual Model will gain adherents more rapidly than The Medical Model.

The Great Psychotherapy Debate has taken me about a year to get through. I haven’t been able to digest all the parts of The Contextual Model. I feel uneasy in regards to what it suggests about the role that specific ingredients play in psychotherapy. But perhaps my concerns there are tangent to what The Contextual Model actually says. The aim of The Contextual Model is to change our focus so that we can more reliably improve outcomes in psychotherapy. I’m on this ride so let’s see where this paradigm shift takes us.