Blog

Art and Science I: Please hold the Science

When I bring up the research from clinical psychology on outcomes of psychotherapy, other therapists say to me, “Psychotherapy is an art and a science.” Yet I’ve had one colleague say to me, “Science can’t tell us anything since it’s always changing its mind.” Another told me, “Science cannot reveal anything about therapy because therapy is about human relationships...”

I was at a cafeteria and ordered psychotherapy without science. The waiter said, “Sorry, we’re all out of science. Is psychotherapy without art okay?”

I

When I bring up the research from clinical psychology on outcomes of psychotherapy other therapists say to me, “psychotherapy is an art and a science.” Yet I’ve had one colleague say to me, “science can’t tell us anything since it’s always changing it’s mind.” Another told me, “science cannot reveal anything about therapy because therapy is about human relationships.” These are statements of “psychotherapy without science.”

I try to spend time getting to know the scientific, empirical, naturalistic paradigm as I believe it is the best tool to predict what will happen and is thus essential for determining how to act. Fortunately, there are groups of clinicians who are interested in the difficult exploration of researching the outcomes of psychotherapy and how it might help us understand how to actually be helpful rather than just intending to be helpful.

II

In the 50s, Hans Eysenck took a hard shot across the bow of our field by publishing a paper examining the evidence of whether psychotherapy helped a group of people with (what were called at the time) neurotic disorders. He looked at the evidence he collected and concluded that psychotherapy didn’t work! This led to a wave of responses and the application of Meta Analysis to studies on psychotherapy in a seminal work by Smith and Glass, “Meta-Analysis of Psychotherapy Outcome Studies.” Their expansive study contradicted Eysenck, concluding that psychotherapy had a demonstrable and significant positive effect with about 75% of people who were treated better off than those who did not receive treatment.

Today, the American Psychological Association has a statement with references to the extensive evidence covering decades of research which recognizes the well established effectiveness of psychotherapy. I have to explain a little about how they determine this. Psychotherapy’s effectiveness in helping people is assessed in a number of ways: self report, other report, clinician assessment, or metrics such as number of hospital visits or number of suicide attempts. It is measured in “effect size,” a measure of the distance between the means of two groups measured in standard deviations. In almost any way we assess psychotherapy, the effect size comes out at around 0.8, which is considered a large effect size and corresponds to 79% of the treated being better off than the untreated. This means the outcome of psychotherapy is similar to well established medical interventions such as coronary bypass surgery, arthritis medication, and AZT for AIDS.

Psychotherapy works.

III

After graduating with my master’s degree I found myself working in a group practice in New York. A friend from my clinical supervision group turned me on to a podcast about common factors theory. In the podcast, they suggested there was good evidence that the specific things said in therapy were not what determined outcomes but rather there was something else that was common to many different styles of psychotherapy that seems to determine outcomes. This led me to the authoritative book on the matter, The Heart and Soul of Change: Delivering What Works In Therapy. The evidence was solid and my confidence was shaken… I spent so much time in graduate school learning what to say and what not to say and those ‘specific ingredients’ didn’t seem to matter! I felt as though I had been misled… as though I was misguided in my work as a clinician. My clients noticed the change in me and half of them dropped me as their therapist.

I found myself at a loss. We have many pretenses about what it means to say that science supports psychotherapy… or that psychotherapy is scientific. But the research on outcomes seems to show that the specific ingredients in what we say aren’t what makes the difference. So why do we spend so much time and effort on “Evidence Based Treatments” that teach you what to say?

IV

I’ve long felt reluctant to discuss what actually seems to account for the outcomes in psychotherapy. There’s this threat that revealing it might take its power away. If we peek behind the curtain to see the wizard, does he lose his power? Part of this is due to the initial conclusion I drew from reading The Heart and Soul of Change: if there isn’t a difference in outcomes between the wildly divergent styles of psychotherapy, could it be that it’s merely a placebo?

The different styles of psychotherapy all contain essential common factors that help people change. This is one of the areas of research that Bruce Wampold focuses on. In a recent paper he discusses his finding that common factors predicts outcomes better than the specific ingredients that evidence based treatments focus on. Because of this, Wampold proposes we think about psychotherapy through a contextual model (which focuses on the healing relationship) rather than a medical model (which focuses on providing the treatment which heals). His research shows that the better we deliver the parts of the contextual model, the better the outcomes.

This is where I get perplexed. Is this how a placebo works? Does that word fit at all at this point or is it a concept out of place?

V

A few weeks ago I got to spend some time with Scott Alexander of SlateStarCodex. While talking to him about what makes psychotherapy work, I came upon another way to think about it. Maybe different styles of psychotherapy are all good enough approximations for our underlying psychology, are not fundamentally different, and thus something like a transtheoretical interpretation is true. That is to say, the underlying similarities between therapeutic modalities in The Handbook of Psychotherapy Integration could be the right interpretation for why psychotherapy works.

I was eager for a chance to ask a researcher I really respect about this. At the Los Angeles County Psychological Association’s annual convention this year, the speaker was Scott D Miller. As one of the authors of The Heart and Soul of Change, he is a major player in the search for the answers to, “what makes psychotherapy work?” and “how can we make it work better?” After his talk, I got the chance to sit down and speak with him.

When I asked him whether psychotherapy was a placebo or whether all the styles of psychotherapy are fundamentally the same, he gave me a response I’m still working to digest. He said, “That kind of thinking continues to look at it through the medical model. I’m only interested in what better facilitates the process of healing.” We went back and forth in our discussion regarding whether psychotherapy has “lost its magick,” with him making impassioned appeals for bringing the art back into the science. He believes we’re too locked into “psychotherapy without art.”

Miller argues that we shouldn’t see ourselves in the narrow profession of ‘psychotherapy’ but in the broader profession of ‘healing.’ This makes me recall reading On Being a Therapist during my master’s program where Jeffrey Kottler romantically describes therapy as a progression of shamanism. Surely the pragmatic philosophy of William James must be driving these people... they have an incredible openness to The Varieties of Religious Experience in order to achieve their goals!

But that’s not the kind of person I am.

VI

I imagine there may be different epistemic personalities. There are people who want everything to be exacting and there are people who can go with the flow and accept ambiguity. Alan Watts has a talk where he refers to this, dividing people as either "prickles" or "goo":

I imagine these personalities leave us with predilections for different cultural projects like science or mysticism, analytic philosophy or continental philosophy.

I’m all prickles. I identify with debunkers like James Randi or Carl Sagan... something about them clicks with my own inner frustrations and anxieties. I am frustrated with the claims people make based on insufficient evidence because of the potential to mislead or harm others. I am anxious about being misled or deceived myself.

And yet there is something to be said for the pragmatists in philosophy for their attempts to resolve the space between prickles and goo. The pragmatist appeal to a coherentist worldview avoids the problems of skepticism we run into when we undertake the prickly Aristotelian project of deriving a foundation from first principles. I have spent a bit of time each week this year trying to better understand the pragmatic underpinnings of the philosopher of science, Willard Van Orman Quine. Quine is quite prickly, describing philosophy as continuous with science and the exploration of science as occurring from within itself with its own tools. And yet he describes science as naught more than another human project, which feels like a gooey way to describe it.

Looking out on the field of psychotherapy from within the philosophy of science I see a problem with our present Research Programme of Evidence Based Practices. Evidence Based Practices rely on conceptualizing psychotherapy with the medical model, where we try to determine which specific ingredients the client’s problem calls for. The research and writing of clinicians like Miller and Wampold directly contradict the utility of specific ingredients, a core part of that model. They show the pragmatic utility of the contextual model in research such as this recent piece by Chow which demonstrates that we can achieve better outcomes when we focus on changing ourselves as clinicians to fit the context in which healing occurs for the client.

This is the stuff scientific revolutions are made of. With such a profound shift in thinking, I still struggle to fit it into my worldview. But I know that as a prickly person, I’m committed to where the evidence leads me. And that as long as I am a clinician, I’m committed to being helpful.

Anxiety Part One: “What It’s Like”

Emotions are tricky - they’re like colors. Understanding facts about colors doesn’t seem to give us all the information...

“In the time of chimpanzees,

I was a monkey.” - Beck

I

Emotions are tricky - they’re like colors. Understanding facts about colors doesn’t seem to give us all the information. I can be raised in a darkened room and be taught about wavelength of light, additive color theory, subtractive color theory, the history of the use of color and pigment in art and photography. Yet, once I leave the darkened room there’s still information in what it’s like to experience the color. Philosophy calls these individual bits of subjective experience “qualia.”

Discussing the “what it’s like” of experience activates the self-observer and works to increase self-awareness. Bernard Beitman describes increasing the capacity for self-awareness as one of the core processes of psychotherapy. Cognitive Behavioral therapists call it identifying thoughts, feelings and beliefs. Psychoanalysts call this development of awareness “insight.” The development of self-awareness is not circumscribed to psychotherapy. Buddhists see it as a practice called mindfulness. The Stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius described self-seeing and self-analyzing as a virtue of the rational soul.

There is a well of knowledge to be gained in exploring what it’s like. This is not information we can quickly teach or transfer. I sometimes like to think this kind of knowledge is difficult to transfer because we find it hard to remember what it’s like to not know. But it’s actually that this knowledge is experiential, a posteriori knowledge that can only be gained by having a number of experiences which contrast with each other. Experiential knowledge can be large and conceptual, making it difficult to transfer because “concept shaped holes can be impossible to notice.”

If I were anxious, would I know it? Perhaps I notice some parts of anxiety but not others. It’s also possible that I can go without naming my experience “anxiety” due to a conceptual bucketing error. I could be misconstruing anxiety as something only people with more serious problems experience. Fear, stress and anxiety are music that every human mind performs. Since everyone experiences them, it can be difficult to tell what it would be like if I was experiencing these more often, more intensely, or for longer periods of time than others. When we don’t notice anxiety, we are acting like the proverbial fish who incredulously asks, “what the hell is water?”

II

When I instruct people to look for anxiety, it often feels counter intuitive to even begin this exploration. “Didn’t I learn this in kindergarten? I saw the poster with the drawings of the feelings! Since then, I’ve been commander of my ship. I sit at the control panels of my mind and have a perfect readout of the quality of my mind. Accurate. Clear. Discrete.”

And yet, we observe again and again that it is possible to be unaware of one’s emotional experience. I’m sure you’ve met someone who is unaware of their present emotions. They sound like this: “ANGRY? I’m not ANGRY!”

This occurs because our attention tracks a limited amount of our conscious perceptions and thoughts. We do not and cannot keep track of all the things which contribute to our emotional states. In The Feeling of What Happens, neuroscientist Antonio Damasio puts it like this,

“[W]e often realize quite suddenly, in a given situation, that we feel anxious or uncomfortabie, pleased or relaxed, and it is apparent that the particular state of feeling we know then has not begun on the moment of knowing but rather sometime before. Neither the feeling state nor the emotion that led to it have been "in consciousness," and yet they have been unfolding as biological processes.” (p 36)

It is possible to be unaware and it is possible to gain awareness. This ability of monitoring and discerning feelings in ourselves and others is referred to as Emotional Intelligence (EI) or Emotional Competence (EC). These research programs are tied to the idea that it’s possible for us to be unaware of what we’re feeling. And while most therapists probably accept the concept of Emotional Intelligence/Competence uncritically (it’s one of the things we all try to cultivate in psychotherapy), there are interesting claims and controversies that I will have to leave to explore in another series of posts.

III

Anxiety is a fear, worry or dread about what might occur. The quality of anxiety can be similar whether the threat is physical, social or emotional. It’s an internal tension and uneasiness. It modulates our behavior in a complicated way. It can help us avoid frightening situations, it can motivate us to work on our goals, or it can impair us from being able to move and act in the world. It becomes a problem when it feels out of control, overwhelming, out of proportion to the situation, and interferes with living.

It’s common to discover anxiety problems in children, who don’t have the same practice naming their feelings, by observing their expression of the somatic symptoms associated with anxiety:

“They appear uneasy, seeming at times to be uncomfortable inside their own skin. Commonly, these youngsters report profuse sweating, light-headedness, dizziness, muscle tension, stomach distress, increased heart rates, breathlessness, and bowel irregularities. … They may say that they feel “fluttery” "or “jittery” or “jumpy.” We have heard youngsters report anxiety by saying they feel “yucky” or “weird” inside.” (Clinical Practice of Cognitive Therapy with Children and Adolescents, p 218)

In adults the altered quality of thoughts that comes with anxiety is more frequently noted: rumination, a mental focus that’s hard to tear away from the distressing thought; perseveration, mentally revisiting the same worry over and over; cogitation, obsessive consideration about what could happen. These qualities of anxiety are part of what leads to having difficulty concentrating or functioning in certain situations or during certain periods.

Adults still have the physical symptoms of anxiety but describe them differently than children. Anxious adults have muscle tension and feel keyed up or on edge in ways that leave them exhausted and sore. They sometimes complain of digestive problems and headaches. They may have a hard time turning off the thoughts to get to sleep. The unpleasantness of anxiety symptoms contribute to the development of avoidance of the subject of the worry.

Since anxiety is an emotion that everyone can and does experience to varying degrees, it’s easy to lose track of just how unpleasant and disabling anxiety can be. Anxiety disorders are common mental health issues, affecting ~10% of the population of western countries but they are highly treatable.

There’s a big question regarding what’s psychologically normal and what’s a problem. In the US, the nosological manual we use to divide up and categorize pathology is the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. The Fifth Edition (DSM-5) of this manual was released in 2013 and its Anxiety Disorders section covers phobias, social anxiety, generalized anxiety and panic. The various anxiety disorders are united by feelings of anxiety or fear but distinguished by the particularities of how these feelings present. Some are related to exaggerated fear, as experienced by those coping with phobias and social anxiety. Other presentations, like generalized anxiety, involve a sort of continuous “anxious misery,” while panic disorder is characterized by discrete, short attacks of anxiety that can become a subject of fear themselves.

I find one of the criteria for Generalized Anxiety from the DSM strangely comforting in its brevity: “[I find] it difficult to control the worry.” (DSM-5 p 222)

The DSM-5 makes the distinction between fear and anxiety by stating, “Fear is the emotional response to real or perceived imminent threat, whereas anxiety is the anticipation of a future threat.” (DSM-5 p189) That is to say that fear requires a cue, but anxiety does not. The two states are qualitatively similar, both involve responses to threats, increased tension in the body and similar changes to qualities in our mind like attention, but we can be anxious with little but our own thoughts. Pensive regret and feelings of foreboding that lead my body to freak out can happen when I’m all by my lonesome. These negative emotions and autonomic arousal is what is presenting in an exaggerated form in generalized anxiety and panic disorder. So while there’s disagreement about how to divide them up and clump them together, for the purposes of exploring anxiety, we’ll start with clumping.

These disorders are related through underlying brain circuits, physiological responses, behavioral responses, and qualitatively similar subjective experiences. It’s helpful to distinguish these factors as they do not necessarily all act in perfect concert. In follow up posts, I’ll be discussing theories of emotion, neurobiology, personality, epidemiology, historical perspectives, adaptiveness, and treatments in the hopes of gaining a deeper understanding of what it’s like and how to cope with being an anxious ape like myself.

“Insofar as we're smart enough to have invented this stuff and stupid enough to fall for it we have the potential to be wise enough to keep the stuff in perspective.” - Robert M Sapolsky

Recommended by AstralCodexTen SlateStarCodex Psychiat-List

Scott Alexander is a psychiatrist on the West Coast who blogs about science, medicine, philosophy, politics, and futurism. His blog is one I’ve followed for a few years now, and I find it to be one of the best sources for dispassionate and well-informed takes on difficult subjects which do not admit to easy answers. His writing demonstrates how to approach questions in a way that improves the accuracy of our beliefs and the application of our values...

Find my Psychiat-List listing here!

Scott Alexander is a psychiatrist on the west coast who blogs about science, medicine, philosophy, politics and futurism. His blog is one I’ve followed for a few years now and I find it to be one of the best sources for dispassionate and well informed takes on difficult subjects which do not admit to easy answers. His writing demonstrates how to approach questions in a way that improves the accuracy of our beliefs and the application of our values.

I’m delighted to have been recommended on his list of mental health professionals! You can find the whole list here: https://psychiatlist.astralcodexten.com/

Frequently Asked Questions About Drugs and Addiction

Is it normal to use drugs? We see the drive to alter consciousness across time and cultures. Every culture has norms and rituals for preparing and using psychoactive substances. As a Human Universal, it’s hard to say that altering consciousness is not normal behavior...

Is it normal to use drugs?

We see the drive to alter consciousness across time and cultures. Every culture has norms and rituals for preparing and using psychoactive substances. As a Human Universal, it’s hard to say that altering consciousness is not normal behavior.

Is alcohol a drug?

Yes.

What is addiction?

The mental health field in the United States is moving away from the term “addiction” and towards discussing “substance use disorders.” Substance Use Disorders are when someone experiences some negative consequences like loss of control, changes in social behavior, and health consequences related to a substance. About 1 in 9 people who use substances meet the criteria for a substance use disorder.

Many people can use substances in an acceptable way and cut back when their use negatively affects them. Addiction is when someone finds they continue to use despite negative consequences and despite the desire to stop.

Please also check the American Society of Addiction Medicine’s page on the definition of addiction as it is an excellent resource.

Why can't people just choose to stop?

Addiction is a disease of the brain that affects its ability to interpret and recall pleasure and pain. The misinterpretation of pleasure and pain affects the part of the brain that makes choices. Over time, the faulty recollection of pleasure and pain leads to lack of motivation to change and a belief structure that supports the addictive behavior.

Why is addiction treatment important?

Addiction treatment isn't there for people who are comfortable with their substance use. Addiction treatment is there for people who find they struggle to cut back on their own and need help. Studies have found that spending money on evidence based addiction treatment is far more effective at reducing costs to society than trying to stop the inflow of drugs or enforcing punitive drug laws.

Can anyone become addicted?

There are many genetic and environmental factors that contribute to addiction. It is possible that with repeated exposure to addictive substances or behaviors that anyone can become an addict. So while having family members who deal with addiction is a good sign you may experience addiction, not having family members who deal with addiction is not a guarantee that you will not experience addiction.

Isn't calling addiction a disease just an excuse?

We know addiction is a disease because it comes from predictable stressors, causes predictable symptoms, and benefits in predictable ways from treatment. Calling addiction a disease explains the behaviors we see as symptoms of a substance use disorder, but doesn't excuse them.

No one chose whether they are susceptible to addiction. But almost everyone dealing with substance use problems have moments of clarity where they notice their behavior around their use is a problem. Recognizing that addictive behavior has become a problem entails being responsible for getting appropriate help.

Are addicts just bad people?

No. The fields of medicine and health have only recently begun to view addiction as a problem within their scope - we are still in the early stages of recovering from a century of viewing addiction as a criminal justice problem. Because it's a long-stigmatized problem, a large majority with addiction problems do not seek out treatment.

People dealing with addiction often behave badly when they are actively in addiction. The drug has become their brain's survival priority. With their brain sending overwhelming emotional signals to "get the drug, it’s the most important thing!" many people behave in reprehensible ways and do things against their moral codes.

The more we understand addiction as a disease, the more we will understand the behavior of people suffering from addiction as symptoms. The behavior of addicts typically goes away with predictable treatments, which lends credence to the notion that they are patients dealing with symptoms, not bad people suffering from moral failings. If we can discuss addiction in a way that brings less shame to those suffering from it, we allow more people to get help.

How do I know if I have a problem?

If you’re bothered by how preoccupied you are with drinking or getting high or struggle with reducing negative behaviors related to substances that lead you to be defensive to others and latch onto stories to justify your use to yourself then it may be wise to discuss your experience with someone who has experience diagnosing and treating substance use disorders.

What if I’m interested in changing my relationship with some substances but not interested in abstinence?

We can have different relationships with different substances. Abstinence is the right option for some people at some points but it certainly isn’t the only option. Others may want to be completely sober from one substance but not from others. Some find that they are able to achieve their goals by moderating. Treatment is helpful for people in various situations with various goals.

Is recovery from addiction possible?

Recovery from addiction is about changing the beliefs, attitudes and behaviors that led to and maintained the problem. Recovery is a long-term process. There are no quick cures nor is there just one way to get into recovery but those who have the desire and willingness to put in the work do recover.

Evidence Based Wellness Choices to Make Life Better

To best understand the role of diet, exercise, and sleep, begin with a detailed journal. Using an app like MyFitnessPal is a quick way to start a food journal. Documenting is an excellent way to learn calorie and nutrition content and gain insight regarding what your choices really entail...

1. To Best Understand The Role of Diet, Exercise and Sleep Begin with a Detailed Journal. Using an app like MyFitnessPal is a quick way to start a food journal. Documenting is an excellent way to learn calorie and nutrition content and gain insight regarding what your choices really entail. Keeping track is the best way to learn what gets in the way and what actually works for you.

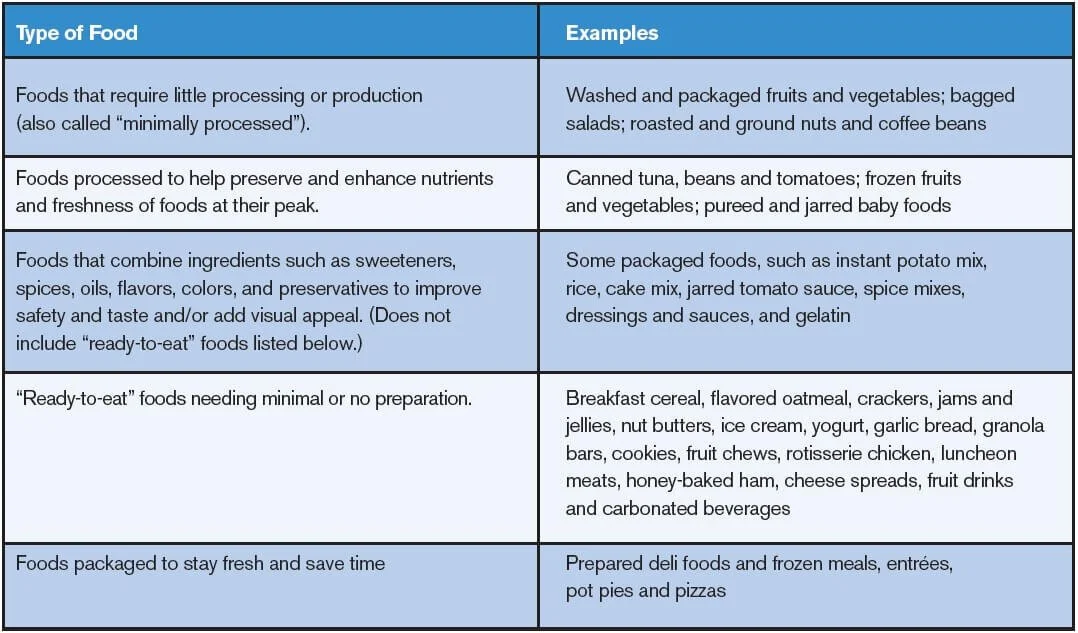

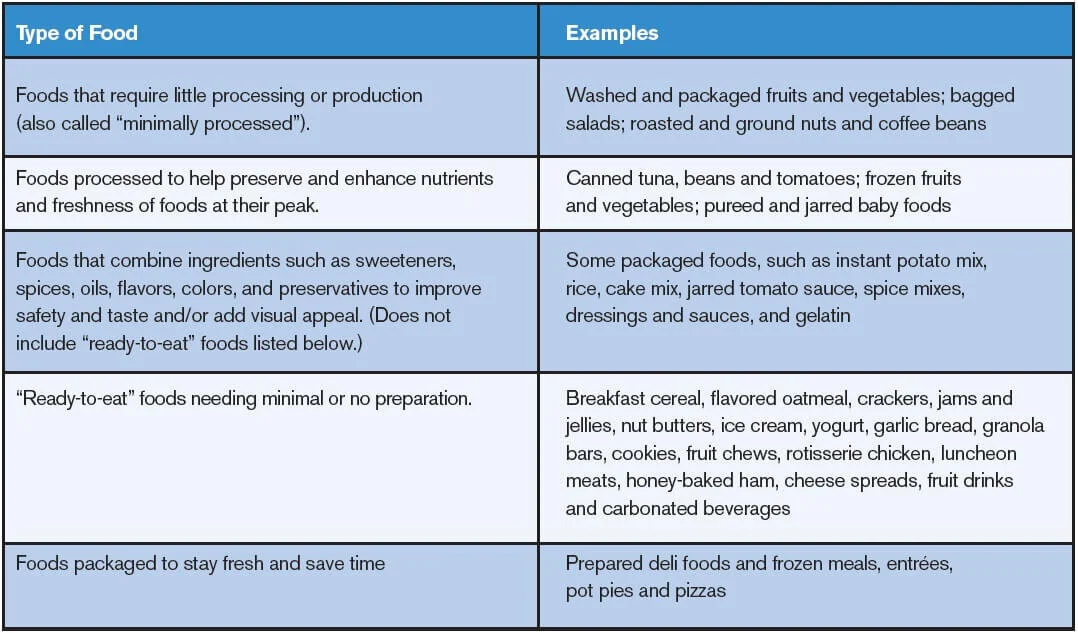

2. Eat Real Food. Comparisons of diets have discovered there is no one solution to “the best diet.” However comparative diet researchers, Katz and Meller, conclude that, “A diet of minimally processed foods close to nature, predominantly plants, is decisively associated with health promotion and disease prevention.”[1] Processed food is food that is changed in any way before it’s made available to eat including freezing, canning, salting or drying.

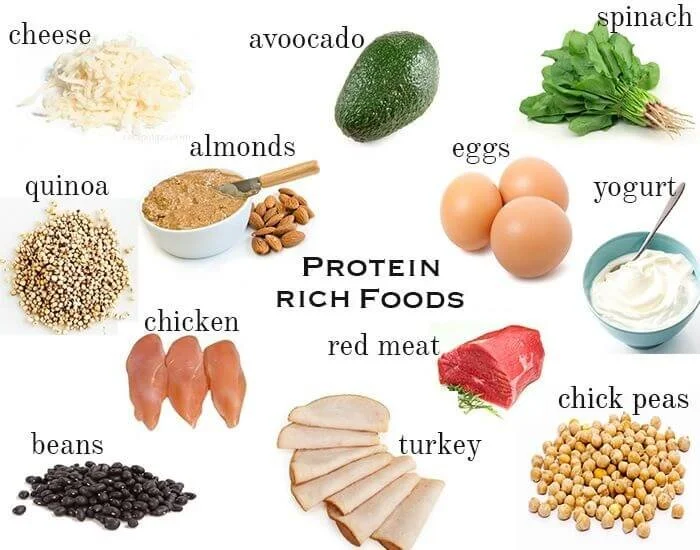

3. Control Appetite by Eating Nutrient Rich Sources of Protein. Eating carbohydrates can make you feel hunger sooner than eating more nutritious food.[2] Eating foods that make you feel full is an important aspect of maintaining a healthy diet. Paddon-Jones et al., state in their 2008 article, “protein generally increases satiety to a greater extent than carbohydrate or fat and may facilitate a reduction in energy consumption.”[3]

4. Engage in Vigorous, Meaningful Physical Activity. Find or pick a physical activity that captures your interest. It can be as simple as a daily walk or a complicated as competitive fencing. Keep yourself involved by making it a habit, making it part of your routine or commit by signing up for groups or classes. Schedule when you’re going to do it throughout the week and commit to going beforehand rather than leaving the decision up to the moment.

5. Manage Sleep with Consistent Routine and Schedule. Limiting daytime naps to 30 minutes, avoiding caffeine for at least 6 hours before bedtime, and engaging in 10 minutes of daily exercise has been shown to improve quality of nighttime sleep. Get out in the sun during the day to encourage a healthy sleep-wake cycle. Develop a bedtime routine such as taking a bath, stretching, or reading. Avoid screens and emotionally stimulating material in the evening. Taking too long to fall asleep at night is a sign you should evaluate your habits as you approach bedtime.[4]

[1] Katz, D. L., & Meller, S. (2014). Can we say what diet is best for health?. Annual review of public health, 35, 83-103.

[2] Poppitt, S. D. (2013). Carbohydrates and satiety. In Satiation, satiety and the control of food intake (pp. 166-181). Woodhead Publishing.

[3] Paddon-Jones, D., Westman, E., Mattes, R. D., Wolfe, R. R., Astrup, A., & Westerterp-Plantenga, M. (2008). Protein, weight management, and satiety. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 87(5), 1558S-1561S.